"The Housewife" Who Became President But Couldn't Change Nicaragua

The history of 20th-century Latin America is predominantly a history of men: dictators in uniform and bearded revolutionaries. But in Nicaragua, a moment once came when the fate of the nation rested in the hands of a woman who never sought power. Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, known simply as "Doña Violeta," became a symbol of reconciliation in the country. We tell the story of how a housewife won and tried to create democracy.

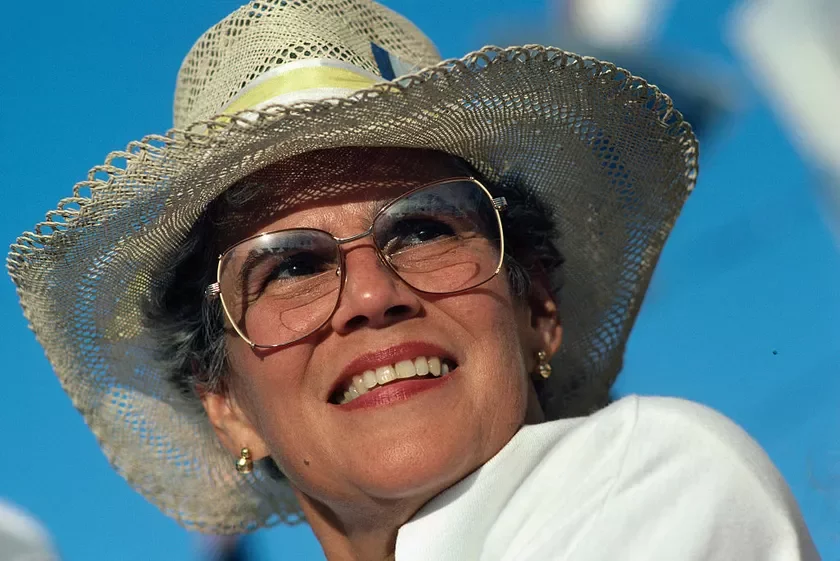

President of Nicaragua, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro. Photo: Bill Gentile / CORBIS / Corbis via Getty Images

When Violeta Barrios Torres was born on October 18, 1929, in the small southern town of Rivas, near the border with Costa Rica, Nicaragua was already a country with deep wounds. By then, it had existed as an independent republic for almost a century, but this "independence" remained conditional.

The country was de facto under the control of the United States. Internally, the country was torn by the struggle between two traditional elites: liberals from León and conservatives from Granada. For long decades, these two forces replaced each other, with coups and civil wars being common.

Violeta was born into a family of wealthy landowners who belonged to the conservative elite. Her childhood unfolded against the backdrop of the Great Depression, which plummeted the price of coffee — the country's main wealth, and against the backdrop of a guerrilla war in the mountains waged against American occupiers by Augusto César Sandino, for whose head the Americans offered a $100,000 reward. By December 1932, the Sandinistas had occupied half of the country's territory.

In early 1933, the American Marines left the country. Before doing so, they created the National Guard and placed the ambitious Anastasio Somoza García at its head. In 1934, Somoza ordered Sandino's assassination, and in 1937, after overthrowing the legitimate president, seized power. Thus, Nicaragua, formally remaining a presidential republic with a constitution and elections, was transformed into a private estate of one family with full military and financial support from the United States.

Violeta, however, grew up away from political turmoil. She began her education in her homeland: attending primary schools in Rivas and Granada, and then enrolling in a college in Managua. Her parents wanted their daughter to improve her English, so they sent her to continue her studies in the USA. This was not higher university education: initially, Violeta studied at a Catholic girls' high school in San Antonio (Texas), and in 1945, she transferred to Blackstone College for Women in Virginia.

In June 1947, news arrived of her father's illness — incurable lung cancer. Although he passed away before Violeta could return home, she still went back to Nicaragua, leaving her studies in the USA unfinished.

In 1949, the girl met Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal. It was a fateful meeting. Pedro Joaquín was a descendant of four Nicaraguan presidents and the editor of the newspaper La Prensa — the only voice that dared to criticize the Somoza dictatorship. They married in December 1950. Violeta thought she was starting a family, but in reality, she was entering a war.

Violeta Barrios de Chamorro. Photo: La Prensa / infobae.com

Wife of a Political Prisoner and Mother (1950—1978)

They married in December 1950. Four children were born into this marriage — Pedro Joaquín, Claudia Lucía, Cristiana, and Carlos Fernando.

In 1952, after the death of his father, Pedro Joaquín inherited the newspaper La Prensa. He took over the management of the publication, and under his editorship, the newspaper became the main mouthpiece of opposition to the Somoza regime. This courage cost the family their peace: between 1952 and 1957, Pedro Joaquín was regularly imprisoned for the content of his publications. The situation escalated in 1957 when he led a failed rebellion against the dictatorship. The result was exile to Costa Rica.

Violeta did not stay in Nicaragua: after settling her children with her mother-in-law, she followed her husband. They lived in exile in Costa Rica for two years, from where Pedro continued to write denunciatory articles against the regime. However, the trials did not end even after their return: as soon as they crossed the Nicaraguan border, Pedro Joaquín was again thrown behind bars.

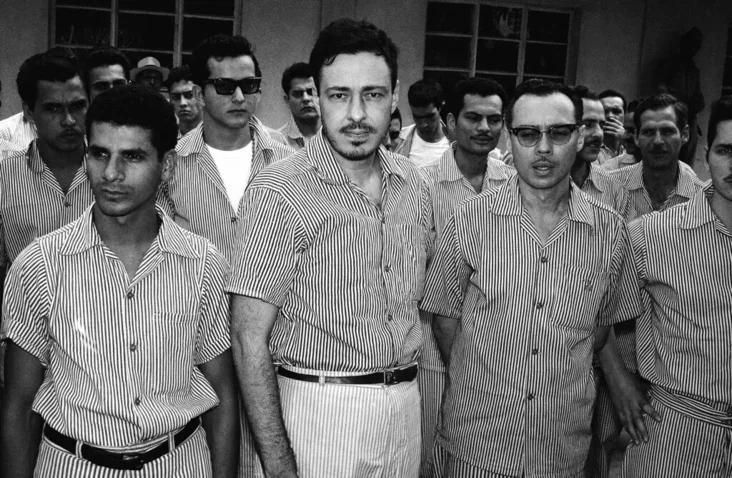

Pedro Joaquín Chamorro (center in the front row) listens to the verdict — 8 years in prison on charges of "treason." December 12, 1959. Photo: AP Photo / Francisco Rivas / La Prensa

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Violeta's life turned into an endless cycle of separations and reunions, now with her husband, now with her children. She always followed him: when he was forced to leave the country, she left the children with relatives and went into exile with Pedro; when he was imprisoned, she returned to the children and regularly visited her husband in prison, bringing packages and hiding notes. It should be noted that the couple's financial survival during these unstable years was provided by income from renting out property that Violeta's mother had given her.

The point of no return came on the morning of January 10, 1978. Pedro Joaquín Chamorro was driving to work in his Saab when his car was blocked and shot by hired assassins. At the time of the tragedy, Violeta was in Miami, preparing for her daughter's wedding. Receiving the terrible news, she urgently returned home to bury her husband and take control of La Prensa.

Pedro Joaquín's death triggered a volcanic eruption. 50,000 people attended his funeral, and many openly accused Anastasio Somoza of the crime. The country, tired of the long rule of the dynasty, began a massive uprising.

Residents of several cities, Masaya, León, and Estelí, with the support of Sandinista guerrillas, managed to expel National Guard units from their areas. In response, Somoza ordered the rebellion to be suppressed by any means necessary.

The United States had long observed the situation with alarm, fearing the arrival of communists, but Somoza's brutality became toxic for Washington. The decisive moment that changed everything was the cold-blooded murder of American journalist Bill Stewart by National Guard soldiers in June 1979 — footage of this shooting was shown worldwide.

Under pressure from public opinion, President Jimmy Carter cut off aid and effectively isolated the regime, acknowledging that it was the dictator's bloody repression that pushed the people into the arms of the Sandinistas.

Deprived of support from its main ally, the Nicaraguan government crumbled, and National Guard commanders fled with Somoza, whom the US initially promised, then denied, asylum in Miami. The rebels victoriously advanced to the capital.

From Hope to Disillusionment: The Sandinista Revolution (1979—1989)

In July 1979, the Somoza regime collapsed. The Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) triumphantly entered Managua. This was a time of euphoria and hope. To gain international recognition and demonstrate that the new government would be democratic and pluralistic, the Sandinistas formed the Government of National Reconstruction. It consisted of five people: three Sandinistas (among whom was the young field commander Daniel Ortega) and two representatives of the "bourgeoisie," one of whom was Violeta Barrios de Chamorro.

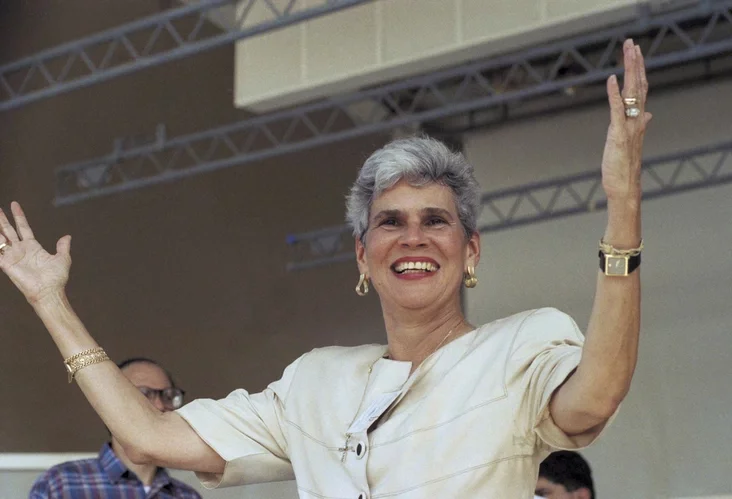

Violeta Barrios de Chamorro — member of the Government of National Reconstruction. July 27, 1979. Photo: AP Photo

Violeta genuinely believed that the revolution would bring the democracy her husband had dreamed of. She even lent the Sandinistas money at the beginning of the transition process. However, illusions quickly faded. Real power was concentrated in the hands of the FSLN's nine-commander National Directorate. Daniel Ortega gradually but steadily consolidated power. He became the Coordinator of the Junta in 1981, and in 1984, he was elected president in elections that the opposition boycotted.

Violeta Chamorro realized that the country was moving towards a Cuban model of socialism: total nationalization, censorship, militarization of society, and a close alliance with the USSR. Planes with Cuban teachers, doctors, and military advisors landed in Managua. The Soviet Union began supplying weapons: T-55 tanks, Mi-24 helicopters, and Kalashnikov assault rifles. Nicaragua became an outpost of the socialist bloc in Central America.

In April 1980, less than a year after the revolution's victory, Violeta Chamorro resigned from the Junta. This was her personal protest against the betrayal of democratic ideals. She returned to La Prensa, which became the main enemy of the new dictatorship. The Sandinistas introduced censorship, limited paper supplies, and incited crowds of "turbas" (Sandinista thugs) against the editorial office.

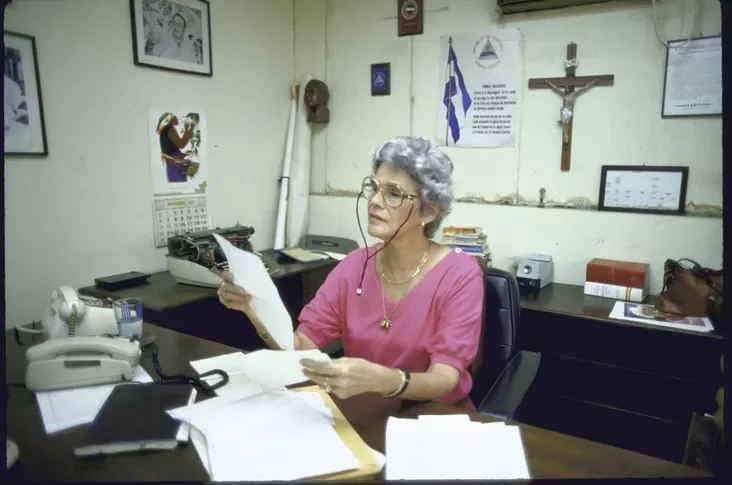

At the editorial office of La Prensa. 1987. Photo: Cindy Karp / Getty Images

In response to Soviet expansion, US President Ronald Reagan began funding and arming the "Contras" — anti-Sandinista rebels. The civil war in Nicaragua became a classic proxy war. In the mountains of Nicaragua, it was decided whose sphere of influence would prevail.

The civil war directly entered the Chamorro home. The family was literally divided by the front line. Pedro Joaquín Jr. and Cristiana continued to work at La Prensa, upholding the line established by their father, while Pedro even left Nicaragua in 1984 to join the armed anti-Sandinista resistance ("Contras").

"Contra" rebels, 1987. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

At the same time, two other children were convinced Sandinistas: Claudia served as ambassador for the revolutionary government in neighboring Costa Rica, and Carlos Fernando became editor-in-chief of the newspaper Barricada — the official organ of the FSLN.

Despite the political chasm between her children, Violeta insisted on keeping the family together. She continued to organize joint dinners, during which an unbreakable rule applied: political affiliations were temporarily set aside for the sake of family harmony.

Coming to Power

By the late 1980s, Nicaragua lay in ruins. The people had endured forty years of Somoza's dictatorship, a decade of civil war and Sandinista rule, and five years of harsh economic sanctions from the United States. The economy was in ruins: per capita income had fallen to levels of 20 years prior, and inflation in 1988 reached an astronomical 33,000%. The Soviet Union itself was undergoing a deep economic crisis and could no longer help. And Daniel Ortega was forced to agree to hold free elections in February 1990.

14 disparate political parties — from communists to conservatives — united in the National Opposition Union (UNO). They needed a candidate who could symbolize unity. After five rounds of intense internal voting, they chose a compromise figure — Violeta Chamorro.

These were absolutely honest elections: the process was monitored by 2,578 international observers, including the UN, the Organization of American States, former US President Jimmy Carter, and former presidents of Colombia, Argentina, and Costa Rica.

Nicaraguan presidential candidate Violeta Chamorro during a visit to the United States. Miami, September 17, 1989. Photo: AP Photo / Kathy Willens, File

Almost all analysts predicted defeat for Violeta Chamorro. The press described her as a wealthy widow who had never engaged in real politics and had no experience in state governance. Sandinista propaganda openly mocked her, calling her simply "the housewife," incapable of running the country, and an "American puppet" receiving millions from the US embassy.

However, precisely what Ortega viewed as her weakness became her greatest strength. In the eyes of the people, she was not a politician, but a mother and a widow. Her "inexperience" in political intrigues was perceived as purity and honesty. Her experience was limited to managing a family (which she managed to preserve despite political divisions among her children) and the newspaper La Prensa under harsh censorship — and this was enough.

In one of Latin America's most religious countries, her image — a woman in white, who also used a wheelchair due to a broken leg — evoked associations with a martyr.

Violeta Chamorro during her election campaign. Photo: Jason Bleibtreu / Sygma / Sygma via Getty Images

The election campaign turned into a battle of symbols. Daniel Ortega had unlimited administrative and power resources and spent enormous sums, behaving like the master of the situation. He chose the "fighting rooster" (gallo ennavajado) as the symbol of his campaign.

Violeta, however, did not promise economic miracles. Her platform rested on a simple, purely feminine and maternal appeal that struck at the heart of the people: she promised to restore peace. "I don't want your sons to be taken to war" — these words hit harder than Ortega's slogans.

Daniel Ortega during the 1990 presidential election campaign. Photo: Jean-Louis Atlan / Sygma via Getty Images

On February 25, 1990, a political earthquake occurred. Contrary to the skeptics' predictions, "the housewife" Violeta Barrios de Chamorro defeated "commander" Ortega, receiving 54.7% of the votes and becoming the first elected female president in the Americas. Nicaraguans voted not for a political program, but against war and fear.

Daniel Ortega, shocked and humiliated by his defeat to a woman he didn't take seriously, was forced to acknowledge the results. However, the transition period was marred by the so-called "La Piñata Sandinista" — a chaotic looting of state property by FSLN functionaries.

And on the morning after the elections, Ortega uttered an ominous phrase that determined the country's future: "We are handing over the government, but not power. We will govern from below."

Presidency (1990—1997)

On April 25, 1990, Violeta Chamorro took office as the first freely elected female president in the history of the Americas. But the country she inherited was divided and full of armed people: key security forces, courts, trade unions, and a significant part of the state apparatus remained under the influence of the Sandinistas, who had lost the elections; the UNO coalition, which brought Chamorro to power, was an unreliable support, as it consisted of both leftists and extreme rightists.

Her entire project rested on one thing: stopping the war, because without it, nothing else would work. On her very first day, Chamorro abolished military conscription. Demobilization and a sharp reduction of the army began: the army was reduced significantly, becoming much smaller in number and less politicized. In parallel, the "Contras" were disbanded and effectively disarmed: without an adversary, the Sandinistas lost their pretext for continuing the war.

To avoid opening a new cycle of revenge, Chamorro declared unconditional amnesties for political crimes of the 1980s. Weapons were collected from both sides, including through "buyback" programs. Collected automatic rifles and heavy equipment were symbolically encased in concrete in the "Peace Park" in Managua.

AK-47 assault rifles covered in cement at Peace Park. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Demobilization had a downside: about 70,000 soldiers and war participants were left without jobs. To ease tensions, Chamorro integrated some former "Contras" into the rural police and created a Civilian Inspectorate to handle complaints about police abuses and human rights violations.

Another "mine" was land: the government preserved the Sandinista agrarian reform and partially expanded land redistribution, including on the Caribbean coast, to meet the demands of veterans. This sparked conflicts with indigenous communities. Disputes over property in the courts dragged on for years.

Within UNO, some demanded to "squeeze out" the Sandinistas from all institutions. Vice President Virgilio Godoy and Managua Mayor Arnoldo Alemán advocated for a hardline approach.

Chamorro made a move that angered the right but stabilized the country: she kept Humberto Ortega (Daniel's brother) in the army leadership, effectively maintaining control over the military through compromise. The right called this step a "capitulation," but it helped prevent a coup. She also included several FSLN representatives in the government, including in agrarian policy — as a sign of reconciliation.

After her victory, the US lifted the embargo and promised aid, helping with loans to the IMF and the World Bank, but the scale of support was much smaller than the needs of a country ravaged by civil war.

Chamorro withdrew the lawsuit against the US at the International Court in The Hague — a case in which Nicaragua sought compensation for Washington's support for anti-Sandinista rebels and the mining of its ports. However, even this didn't save her: in 1992, ultraright Senator Jesse Helms succeeded in cutting American aid, accusing Managua that the Sandinistas still influenced the state.

Nicaraguan President Violeta Chamorro and Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo (left) with US President Bill Clinton on their way to a group photo session of participants at the Summit of the Americas in Miami, USA. December 10, 1994. Photo: AP Photo / Marcy Nighswander

Economic Problems After the Changes

When the issue of war gradually receded from the agenda, the economy became the main problem. Chamorro inherited an economy devastated by war and hyperinflation. The government adopted a neoliberal scheme: privatization, reduction of state spending, abolition of subsidies. A state holding company, CORNAP, was created, uniting dozens of enterprises nationalized under the Sandinistas. The task was ambitious: to sell most of these assets to private investors, obtain foreign currency, and reduce the state sector.

At the same time, a new currency was introduced — the golden córdoba, pegged to the dollar, and subsidies on basic products were abolished. This helped to curb inflation, but prices for bus tickets, basic products, and utilities sharply increased.

Already in 1991, a wave of mass strikes swept across the country. Chamorro made an atypical compromise: she recognized the right of workers to receive 25% of the shares of privatized enterprises — which irritated the right-wing in UNO and some foreign partners.

In parallel, the government conducted difficult negotiations on the write-off and restructuring of foreign debt. A large part of the debts was eventually written off or stretched over time, which allowed Nicaragua to access new loans and stop hyperinflation. But this did not mean a quick improvement in life. Budget cuts, the closure of social programs, and a sharp reduction in state spending led to rising unemployment and a deterioration in healthcare and education systems.

In search of food and other still usable items, people rush to a garbage truck at the central landfill of Nicaragua's capital, Managua. May 9, 1996. Photo: Michael Jung / picture alliance via Getty Images

Statistics collected during this period appear contradictory. On the one hand, Nicaragua in the 1990s and 2000s dropped in human development rankings and became the poorest country in the Americas after Haiti. State spending on healthcare per capita in the mid-1990s was several times lower than in the late 1980s.

On the other hand, gradual progress was observed in some areas: child mortality decreased in the 1990s, and average life expectancy increased. In terms of some indicators in rural areas in the second half of the 1990s, there was a slow movement for the better.

But for most people, the daily reality was simple: no jobs, low wages, social guarantees gone, and the promise of "peace and democracy" did not automatically translate into stable income.

Constitutional Crisis of 1995

The most dangerous political explosion occurred in 1995. The 1987 Constitution was written by the Sandinistas for a strong presidential power. Parliament began a process of constitutional reform aimed at limiting the president's powers. Chamorro, believing that the time for such a reform had not yet come, refused to publish the new constitution project approved by parliament in 1995 in the official gazette.

Parliament printed them itself — and the country found itself in a situation of "two constitutions."

After long negotiations, a compromise decision was reached: Chamorro agreed to officially publish the constitutional amendments, and parliament allowed the president to retain several key powers in foreign policy and taxes, refraining from immediately limiting them in practice.

Nicaraguan President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro (center), her son Pedro (left), and mother-in-law Margarita Chamorro (right) during prayer at a religious service in a church in Managua. January 10, 1995. Photo: AP Photo / Anita Baca

Return of Darkness

On January 10, 1997, Violeta Chamorro did what was rare for Nicaragua: she peacefully handed over power to a democratically elected successor — the liberal Arnoldo Alemán — and retired from politics.

After her presidency, she established the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation to support educational projects and press freedom. But her health began to decline, and she gradually lost her memory and connection with reality.

The tragic irony of history is that as Doña Violeta's consciousness faded, the country slowly returned to where she had pulled it from. Daniel Ortega, whom she defeated in 1990, returned to power in 2007 — and step by step began to undermine the democratic institutions that had been built with such difficulty in the 1990s.

Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega (left) embraces Violeta Barrios de Chamorro during his inauguration ceremony in Managua, Nicaragua. January 10, 2007. Photo: Susana Gonzalez / Bloomberg via Getty Images

History came full circle. In 2021, Cristiana Chamorro, who was called one of the strongest opposition figures, was ordered arrested by Ortega; her brother Pedro Joaquín Chamorro also went to prison. Journalist Carlos Fernando was forced to leave the country. La Prensa — a symbol of family history and opposition tradition — also came under attack: on August 13, 2021, police occupied its editorial office.

Violeta herself, bedridden in her Managua home, was no longer aware of this new nightmare. In October 2023, relatives secretly moved her from Nicaragua to Costa Rica to ensure proper medical care and safety in the final days of her life, away from the regime of the man she had once defeated. Violeta Chamorro died on June 14, 2025, at the age of 95.

The story of Violeta Chamorro is important for Belarusians not as an exotic Latin American plot, but as a warning. It shows that exiting dictatorship and violence is not an instant victory or a triumph of justice, but a long and painful process. Compromises and morally difficult decisions do not guarantee success, and failed economic policies can lead to the restoration of an authoritarian regime. Chamorro did not promise miracles. Her main achievement was peace and the peaceful transfer of power. But she failed to build a sustainable democracy.

Her fate testifies: democracy is not established once and for all. Even after free elections, a country can again slide into authoritarianism. For Belarusians, this is a story about how victory is often just the beginning, not the end.

Comments