Bialiatski: The majority of people do not support Lukashenka, I will say that unequivocally

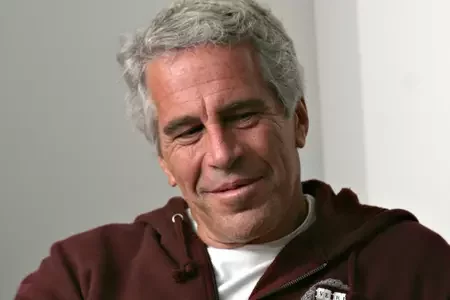

Ales Bialiatski, head of the Viasna Human Rights Center, spent three more years in the Horki colony after being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He was released only after the US lifted sanctions on Belarusian potash. How does the ex-political prisoner himself assess this deal, what does he think about the lifting of sanctions and Babaryka's answers regarding the war in Ukraine and Crimea? About this and more – in a big interview with "Zerkalo".

"How much am I worth? A ton of potash? A thousand tons?"

— How did you learn about the US-Belarus negotiations in the colony? And did you hope that mass releases would begin?

— We need to start with how I ended up in the prison hospital. The saga was quite long – they couldn't take me out for a year. Eventually, I found myself in Kaliadzičy (referring to the hospital at the detention center in the village of the same name. – Ed. note). That was in June. I had leg surgery there. I spent a night in intensive care. The next morning (it was a Saturday, as far as I remember, a day off) they brought me to the ward – and that's when I could reach the radio. I turned it on and heard the news that the first group had been released, that Tsikhanouski and other political prisoners had been set free.

Generally, it's not the first time we've encountered such things, when political prisoners are accumulated, then some bargaining takes place, and then some are released. The first time I was released in 2014 was also in this way (in 2011, Ales Bialiatski was sentenced to 4.5 years in a reinforced-regime colony. – Ed. note). And now, when I heard that the first group had been released, I understood – apparently, the process had begun. Because Siarhei Tsikhanouski, most likely, was perceived by Lukashenka as a personal enemy, whose release would have been very serious for him. This was the first signal.

And when I was brought back to the Horki colony after the hospital, I also felt that the pressure from the administration had decreased. While before I received some violation every month, here they seemed to forget about me for a while. This did not apply to other political prisoners: in our colony there were people convicted [already after Tsikhanouski's release] under Article 411, for "gross violation of internal regulations." Political prisoners also ended up in BURs (reinforced regime barracks, now their equivalent is PKT, cell-type premises). They also ended up in the SHIZA (punishment cells).

— Do you think the deal – sanctions in exchange for releasing people – is a good thing?

— I am filled with conflicting emotions. On the one hand, I am truly happy and glad to be free. I can see my family, my wife, acquaintances, friends, I can truly live in a free country, however trite those words may sound. As they say, "the intoxicating air of freedom," etc. – all these banalities now apply to me. The first day, when I got out of prison in Vilnius, I was literally intoxicated by that air.

But on the other hand, there is, of course, a certain feeling of bitterness, because it's simply an exchange, a trade. So we were traded for potash. How much am I worth? A ton of potash? A thousand tons? You become a bargaining chip. I emphasize again: I very much hope that this is the first step, and that after the release of all political prisoners, there will be further steps towards the democratization of the situation in Belarus. Because otherwise, this exchange, pleasant as it is for me personally, ultimately makes no sense. We need to stop political repression so that people can live more or less freely in the country.

— In your opinion, can and should the European Union also join in, together with the US? Because the most painful sanctions for Lukashenka are, after all, those from the EU.

— I believe that the sanctions policy and the political statements of the European Union, which does not recognize the legitimacy of Lukashenka's rule, the elections of 2020 and 2025, or the constitutional changes that have occurred during this time – this is extremely important so that we do not lose our bearings on what we are building. If we want to live in a normal democratic country, we cannot turn a blind eye to all these transformations for the worse and start lifting sanctions. What are the reasons for lifting them? The release of political prisoners? Well, they'll just round up others. The laws remain the same. Is it really difficult to recruit the next thousand across Belarus from the millions who live there now? We need to achieve fundamental changes in the structure of state governance in Belarus. We need to achieve free elections. Without this, the catastrophes that occurred in 2020 will repeat themselves. Therefore, the principled policy of the European Union in recognizing that Belarus is currently unfree, undemocratic, and under illegitimate rule is extremely important.

Maybe it's unpleasant, maybe it's difficult now. But listen, we endured for more than a decade until the Soviet Union collapsed. Do we need to endure more? Then we will.

Let's see clear prospects of how this might end, and take clear steps, rather than seeking some compromise with actual scoundrels. With people who have committed so many crimes and are not accountable for them in any way. I think that the policy of our neighbors – Lithuania and Poland – towards Belarus, and indeed the entire European Union, is currently the most optimal.

— It seems that Lukashenka slips out of any situation and has been doing so for years. Is it even possible to achieve the goals you are talking about?

— Firstly, you cannot compare the situation he is in now with the one 30 years ago. Because back then he had real support, legitimacy; the elections, as a result of which he became president in 1994, were more or less fair. And indeed, we still had a Soviet-Belarusian society, where many were nostalgic for the Soviet Union. They supported the changes that Lukashenka offered them. We worked in a society where democratically minded people were in the minority. But the situation changed. In 2020, we saw that generations had changed, and the youth, for the most part, are oriented towards Europe. These are people who travel to European countries for holidays, study, or other matters, who would like to live a normal, peaceful, and civilized life, who are not afraid to speak their minds, who highly value their dignity. And we heard this very clearly, especially from 2015 to 2020, when, I believe, the majority of Belarusians began to orient themselves towards Europe.

This is due [among other things] to the fact that our neighbor is the European Union, thanks to the work of our civic activists.

The contacts of hundreds of thousands of Belarusians who have visited Europe bore fruit. People simply began not to understand the authorities, and Lukashenka ceased to be their president. And we heard this in 2020.

Then it became clear that if power is maintained in such a dramatic way as he did, everything simply turns into a dictatorship – a minority holds power, it can be called a gang, a corrupt faction, or a pro-government mafia. But in reality, the majority of people do not support them and Lukashenka. I will say that unequivocally. We saw this in the elections.

And being in the colony, talking to thousands of people during this time... The support is like this (shows minimal level with fingers). That's how few people say something good about him. You won't hear a good word about Lukashenka now. There is no authority, no respect. They look at him as a person who is simply clinging to power by his fingertips.

Many voted for Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. Even among the inmates, among people very far from politics, from Belarusian villages and towns. They don't want him. Everyone is simply fed up with him. Therefore, this regime has no prospects.

Well, as for how all this will change, we'll see. I think there can be many different scenarios. There was an attempt at a peaceful revolution in 2020, which met with rejection, with hostility. I think that by doing so, Lukashenka put an end to his political career. And in general, I would even say, to his memory. Because there are not many people, even among his supporters, who approve of and support the repressions. What will be his legacy after this period ends? I don't think it will be evaluated positively in any way.

"Maybe some other reasons compelled him to speak that way. I don't know everything."

— There is an opinion that if Belarusians had won in 2020 and the power in the country had changed, perhaps there would have been no war with Ukraine. Do you think this is a valid point?

— I think one should be careful with the subjunctive mood. Because you can never account for all factors. It's as if we don't remember the Russian Guard that was standing on the border with Belarus, just waiting for a signal to enter.

Russian President Vladimir Putin stated on August 27, 2020, that Alexander Lukashenka had asked him to form a reserve of law enforcement officers. According to Putin, this reserve was to be used if the situation began to spiral out of control, if "extremist elements crossed certain lines, directly resorted to banditry, started setting cars, houses, banks on fire, attempting to seize administrative buildings, etc." In December, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Belarus concluded a cooperation agreement with Rosgvardiya (Russian National Guard).

It is highly probable that there would have been an occupation of Belarus by Russia. The same as when they tried to violently seize Ukraine. But history cannot be rewritten. What happened can be analyzed, and we can reflect on what mistakes were made. However, I believe that, largely, there were none. There was, perhaps, a certain lack of awareness, inexperience among the people who found themselves at the forefront of change. Somewhere, perhaps, there was slowness, somewhere a lack of resolve and courage.

But I am afraid to make any predictions, like, "if we had done this, we would have won." That's too self-assured an assessment, considering that our political future and, indeed, the entire life of Belarus largely depend on what happens in Russia. As regrettable and paradoxical as it is, we depend on this. And that's why I am very concerned about what is happening with the Russian-Ukrainian war. I would very much like it to end and, in some way, for a transformation to eventually occur in Russia as well. Because it is our neighbor. Lithuanians say: "We really wanted everything to be well with you, because we need a stable Belarus." So, we also need a stable, democratic Russia; we need stable eastern borders. Although no one talks about that now.

— Viktor Babaryka's words during a press conference are now being hotly debated. He gave an interview to Ukrainian blogger Volodymyr Zolkin, who also asked about Crimea. Babaryka did not unequivocally state whose it was, and his answers about the war were also vague. How did you react to his statements?

— I am by no means going to condemn any political prisoner. The most important thing is that the absolute majority endured. It was a very serious blow, and it was very easy to break a person, to morally convince them that there were no prospects, no point in holding a position, to force them to cooperate. Very few went along with this. And this is a great honor for Belarusian political prisoners and for democratic forces in general. We have few defectors. There are some, we won't name them. But they are truly isolated cases. Thousands, tens of thousands of people who fell under the wave of repression endured it with dignity.

As for [Babaryka's] political future... we'll see. People emerged from a very confined space. Perhaps with unstated political accents, having little prior political experience, as they were generally involved in completely different matters. It might be too early to demand mature statements from them.

Although I am also disappointed regarding Crimea and the war with Ukraine. This matter is absolutely clear. Even there, in captivity, you could get enough information by watching "60 Minutes" and the same Skabeyeva (referring to Russian propagandist Olga Skabeyeva), filtering out propagandist nonsense, froth, and based on factual materials, make your own decisions. In the colony, we discussed this. There are more than one or ten people who hold a correct position regarding this conflict, perceive Russia as an aggressor, and worry about Ukraine. Moreover, some of those released from our colony joined the military resistance on Ukraine's side after they were freed. We received information that these people are already fighting in Belarusian units of the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

It's hard to say [why Babaryka spoke that way]. Maybe some other reasons compelled him to speak that way. I don't know everything. These are, I think, questions that can be asked of Viktor himself. Maybe a bit later, not now. Let him recover, come to his senses.

— "Zerkalo" chose the person of the year. It was Mikalai Statkevich. I assume you know about his actions. How do you assess them?

— Noble. And not everyone could have done what he did, of course. But knowing Mikalai for over thirty years, knowing his courageous stance, I understand that only he could have done such a thing. I appreciate that. It is his personal choice to continue the fight in this way. Because when there are political prisoners in a country – politicians, public figures, human rights defenders – it is a clear indicator of what is happening in the country, that there are huge problems with human rights, that there is a dictatorship that keeps political opponents in prisons. Such a path is difficult. One needs incredible fortitude to endure it, and I deeply respect that. And I think that the question of Ukraine and Crimea was never an issue for Mikalai. Because he is a person with a clear, firm position. I very much hope that sooner or later, preferably sooner, he will be free.

— You also returned to Belarus in 2021. Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya's advisor Dzyanis Kuchynski told me how you traveled to Vilnius in the spring and met her at a hotel. When you stated that you would go back to Belarus, she asked if you were scared. You replied: let the regime be scared, – and you went. Soon after, you were detained. Why did you make that choice? Do you regret it?

— It wasn't so much returning as making short business trips. Continuing work in Belarus was a conscious decision. At that time, when mass repressions were already rampant, we, human rights defenders, were involved in providing assistance, assessing the situation, gathering information on who was imprisoned, for how long, where to direct whom – a huge amount of work. We couldn't just drop everything and flee. Part of the organization left – that was our decision, to be able to continue working even in case of arrests.

Ultimately, when they occurred in July 2021, three people were left in detention – myself and my friends Valiantsin Stefanovich and Uladzimir Labkovich.

It was necessary at the time. We couldn't flee. We had to take this blow from the authorities. The imprisonment of human rights defenders was a very strong signal to the European Union and the entire international community that something was wrong in Belarus. Mass repressions were ongoing, journalists, human rights defenders, political and civic activists were being imprisoned. Fleeing was not an option. So we decided to stay. Ultimately, I received ten years in prison, of which I served four and a half. I do not regret that we made that decision then.

— If you had such a choice now, would you go to your homeland?

— Now? In this situation? It's probably better for me to be here, if only because I need to catch my breath, as I've endured this period of constant pressure – moral, psychological, and physical. A person's strength is not limitless; you need to gauge your capabilities and carry as much as you can, so to speak. Returning now is not an option. You would return and be arrested within a few days. Perhaps I will still achieve more here now, but with firm belief that sooner or later we will return there. But preferably sooner, of course.

"I would like to see Lukashenkaism put on trial, and for the people who built this system to get what they deserve."

— In an interview with Deutsche Welle, you compared your first and second terms and noted that the system had become harsher. Do you have an answer as to why it is like this now?

— If you compare all previous detentions that have occurred [in Belarus] non-stop since 1995, there wasn't a single year without political prisoners. But there were five, thirty, after the 2010 elections — about a hundred. But not thousands, as now. Now, a political decision has been made to finally crack down on those sprouts of democracy, democratically-minded activists, journalists, and civil society in Belarus. The decision is unequivocally criminal. This is a crime against its own people, which in no way strengthens either the authority or the capabilities of these authorities. Yes, they will remain for some time. However, I am convinced that they have no serious prospects.

— It's clear with the authorities. But, for example, the perpetrators are ordinary Belarusians. We are all from the same country; why do they go along with this?

— Firstly, people adapt to different situations. Secondly, not everyone in the colony is a sadist; there are some who seek concrete benefits for themselves. Three or four individuals who engage in this make careers out of it; the repressive system of dealing with political prisoners is built upon them. The remaining employees are neutral or even sympathetic.

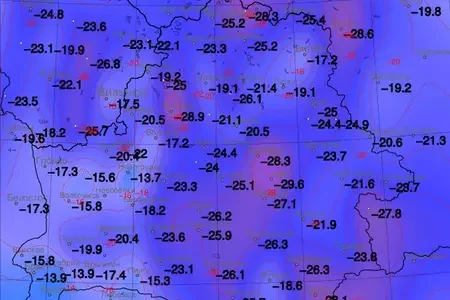

Ideologically convinced people who would beat their chests and declare "I am for Lukashenka"... No, I haven't seen any such people, surprisingly, even there, in the very east of Belarus. The Horki colony. Fourteen kilometers from the Russian border.

— Thousands carried out the repressions. It's not just Lukashenka, Tsertsel, and so on. What do you think should be done with such people if democratic changes occur in Belarus? Lustration, simple reconciliation, or another path?

— Undoubtedly, a process of lustration should take place, as it seems to me. Because if we want to achieve justice, it must apply not only to political prisoners, who will be rehabilitated, but also to the torturers. This is very important. And in what form this will be – that is a question for the future, as there are different ways to resolve the situation.

I would like to see Lukashenkaism put on trial. And for the people who built this system to get what they deserve. I believe that would be fair. As for the form and details – those are nuances.

"I almost shouted there that it was incredible, impossible."

— Who was the first to tell you that you were a Nobel laureate, and how did you react to it?

— It was a very mundane situation. I was in the pre-trial detention center then, going to familiarize myself with the criminal case. We had 210 volumes there; we went every day for a month. And so, on one of those days in October [2022], I was walking – a row of prisoners was standing. And one of them said: "Ales, you supposedly became a Nobel laureate." I didn't believe it, but I became wary – what was this, what rumors were circulating? And I went into the office where the lawyer and investigators were already sitting. Then the lawyer said: yes, indeed, you became a Nobel laureate. Yes, everyone is writing and talking about it. She said this not from herself, but that she had read it in the mass media.

I had a very emotional reaction. I almost shouted there that it was incredible, impossible. The investigator sat and smiled, she had a somewhat foolish look on her face. That day I certainly didn't read any more volumes; instead, I tried to somehow comprehend what had happened.

If you look at the chances [of receiving the prize], they were small. That's how the situation unfolded. And it itself – very importantly – was given to people who fought for freedom. It is not my personal prize; it was a way of drawing attention to the tragic situation with human rights and democracy in Belarus.

— At the moment you realized you were a Nobel laureate, did you think about how Lukashenka would react? Was there no fear that he might intensify repressions, or, conversely, optimism that a Nobel laureate would be released from behind bars?

— No, I remained absolutely calm. You can fantasize a lot. It's better to live based on the situation you are in. So I treated it like, "Well, it is what it is." And as for the position of Lukashenka and the authorities, they tried not to pay any attention to it, to reduce its significance.

In fact, I had to spend three more years in prison after becoming a Nobel laureate, and on general terms. I didn't get any VIP cell. On the contrary, they tried to diminish the importance of this prize and show that it meant nothing to them. To what extent they succeeded – I don't know, because the time a Nobel laureate spends in prison is a challenge to the entire civilized society. And ultimately, this became another reason why I found myself free, because keeping a Nobel laureate in prison is not entirely good.

— What will you do with the monetary part of the prize?

— I have not yet received this money, but I know that it will go towards strengthening the capabilities of my human rights work.

Comments

Згодзен з Панам Бяляцкім, менавіта падтрымкі ў яго няма і амаль ніхто не стане яго абараняць. Але ж і сучасную апазіцыю большасць не падтрымлівае, будзе маной сказаць, што большасць чакае , што яны зменяць Луку. Атрымліваецца, што яго яны церпяць, але ж на апазіцыю не спадзяюцца.