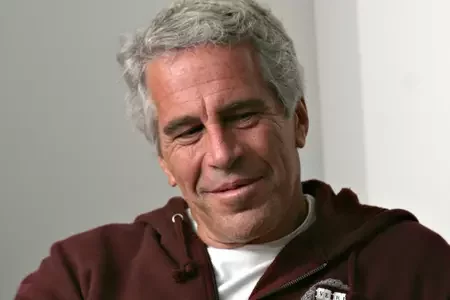

Labkovich: I had no idea what it would actually turn into and what awaited me further in this system

This is a conversation about five years erased from life, and about returning to a changed world. In an interview with "Belsat", Uladzimir Labkovich recalls the day of his detention, talks about being expelled without documents, the practice of "inflating" sentences in prison, the consequences of imprisonment, and what life looks like today after captivity.

"They kept saying, 'You have a life sentence'"

— Tell us about July 14, 2021. Did you have a feeling that day that this story would last for years?

— We, of course, foresaw that our detention was very likely. Approximately 24 hours before that, we last met with the Viasna team that was then in Belarus: Ales Bialiatski, myself, and Valiantsin Stefanovich. We discussed how the organization would act in case of our detention.

On July 14, around six in the morning, law enforcement officers started breaking down my door. I told them through the door that there were three underage children in the apartment, that I would open up, and asked them to come in calmly, without incident. They entered without using physical force — it was a relatively gentle start to my almost five-year ordeal.

They said that if I behaved normally, only three officers and two witnesses would remain. At first, there were a lot of them — the entire stairwell. But they did indeed remove the others.

I offered to send the children to their grandmother so they wouldn't see what was happening. They agreed. My daughter understood everything immediately, and the boys, who were seven years old, asked who these people were. I said they were plumbers — supposedly a pipe had burst overnight. They played along, saying they would fix everything immediately.

That was the last time I saw my children. The next time I saw them was on December 17, 2025, when I got off the bus in Vilnius.

They did not hide the fact that this was an arrest and that I would not return home. They offered to pack essential items. At that stage, the people conducting the search seemed intent on making my future life as easy as possible.

Then the investigator said that this would be for a long time and that I wouldn't go home.

But I didn't feel it would be five years. I thought it would be a matter of a week, a month at most. I had no idea what it would actually turn into and what awaited me further in this system.

— If we go back to December 13, 2025 — at what point did you realize that this was truly a release, and not just another stage?

— The entire year 2025 was the most difficult for me throughout this journey. In 2025, I was transferred from colony No. 17 to a prison regime. From the prison regime, I was transported to the KGB pre-trial detention center, then to pre-trial detention center No. 1 in Kaliadyčy, then to Žodzina prison No. 8. Before that, I had been in Mahilioŭ prison No. 4.

And all this time I was threatened with new criminal cases: a case for organizing an extremist formation, the Human Rights Center "Viasna", and for treason against the homeland, and even the infamous Article 411 — violation of the rules of serving punishment.

All the time they told me that all these releases that were happening were not about me at all: everyone else would be released, but people like me would remain.

And I truly didn't believe it. When new articles keep piling up on you, you understand that the term allotted to you by the court means absolutely nothing, that it is effectively a life sentence. They kept saying, "You have a life sentence."

Until the very last moment, I believed that this was simply such an infiltration, a transfer of those considered the most "malicious" to some separate place where people like me would be held further.

Only when I saw representatives of the Ukrainian authorities, soldiers in uniform with Ukrainian chevrons, when I saw a large Ukrainian flag and emblem above the border crossing building, did I realize that this was too expensive a decoration just to transfer us to some special institution. I understood that this was indeed a transfer to the Ukrainians.

De jure a citizen, de facto — not

— How do you generally assess your "release" in quotation marks — is it an exchange, deportation, liberation, expulsion?

— It's an expulsion from the country. It is absolutely legally unlawful. A citizen of a country cannot be deprived of the possibility to freely return to their country. They cannot be deprived of documents, because the state is obliged to issue them documents and provide legal and material assistance abroad.

But here, effectively, state bodies de facto make you a non-citizen. De jure you are a citizen of the country, but de facto — you are not. The state not only refuses to help you — it generally denies you basic rights associated with citizenship.

I, for example, was expelled from the country without documents. Of the 123 people who were released on December 13, about twenty people were without documents. These included media figures and other individuals. By what criteria they were selected — who with passports, who without — I do not know.

— What are the prospects for considering this case of forced expulsion in international instances — in the UN?

— This is a violation of international UN standards. I believe that if the UN has not yet reacted to this, it must react. But there are no mechanisms that can compel Belarus to fulfill its obligations. Here, Belarus is simply grossly violating the rights of its citizens and grossly renouncing its international obligations.

I am, of course, not a great expert in international law, but it seems to me that, unfortunately, there is no instrument by which Belarus would bear responsibility for its unequivocally unlawful actions from the point of view of human rights and the international obligations it voluntarily assumed within the UN system.

"Before bed I think I'm in prison, and when I wake up, the first thought is that I'm waking up in prison again"

— You fundamentally refuse to talk about what happened to you in captivity. Why?

— I believe it's not the time yet. Currently, there are about 1300 people behind bars. We must be responsible for them and understand that every word we say resonates as pressure on them. And it truly hinders the possibility of that track, which I strongly support, currently being pursued by the Americans, because the most important thing now is to free people.

My situation is not unique. Unfortunately, all people who went through this meat grinder were indeed subjected to torture — both physical and moral. And what happened to us was extremely difficult. It's all still too close, so I ask for more time and a pause.

— What consequences of imprisonment on your health do you feel most strongly now?

— Of course, my time behind bars did not pass without leaving a trace. My health is not good now. For the last month, I have practically been doing nothing but going to the hospital every day, undergoing examinations — everything ends in treatment. Chronic diseases — I have an ulcer, and it makes itself very known.

It must be said that mental health also did not remain without traces. It's still very difficult for me. All the time, as I say, I fall asleep and wake up in prison. Before bed, I think I'm in prison, and when I wake up, the first thought is that I'm waking up in prison again. This, of course, is psychologically quite difficult.

— As a former political prisoner and human rights activist, tell us, what kind of help do political prisoners need in the first months after release?

— It seems to me that everything is very individual. Someone might have very poor health, and it's actually a matter of saving a life. Someone else's health might be much better, but rehabilitation and treatment can still last quite a long time.

The most important thing is moral and psychological support. Warmth, care, attention, so that a person does not remain alone with their thoughts. In a way, it's easier for me because I came to Vilnius, where my family awaits me — my children, my wife. But most people are in a completely different situation.

They are cut off from their relatives who remained in Belarus, and there are big problems even with seeing them. And such people truly need psychological support and help to get out of this personal drama into which they all fell.

Five years for children is an entire epoch

— How did you experience the separation from your family? What turned out to be the most difficult?

— The most difficult are thoughts about the children and my wife, worrying about how they are. And indeed — it's the children growing up. For example, for us adults, five years is a long time, but we haven't changed much in those five years.

But for children, five years is an entire epoch. It's a really huge gap. My daughter was 13 when I went behind bars, and when I got out, she turned 18 literally a week later. She's a completely different person now. I literally got to know her again. We both got to know each other again. She still remembers me, but I never remember her at 18, because for me, life was on pause.

It was a very strong impression for me when, for her 18th birthday, my daughter suggested in the evening that just the two of us go to her favorite cafes and bars in Vilnius. And so I walked around cafes with my already grown-up daughter, she treated me to various drinks, and I understood that she was already 18, that it was okay now. It was a truly new acquaintance with my loved ones.

With the boys, it's a bit simpler, because they were seven, now they are 12, and they haven't lost that childishness yet. They have a lot left that allows me to establish communication with them more quickly. We now do homework, read books, discuss situations, books, films.

Now all my time is dedicated to caring for my family and children, because I truly feel guilty in many ways. It was very hard for them. My wife went through extraordinary trials, including being behind bars herself for some time. I understand how it was for the children — for them, it was a tragedy to be left without both mother and father at the same time.

Therefore, I am trying very hard to catch up on this time now. I dedicate all my free time to my children. Previously, a significant part of my life was occupied by civic activities, now, while there is an opportunity and while colleagues believe that I need a long period of recovery and treatment, I have more free time and spend it with my family.

— At a press conference with former political prisoners in December last year in Vilnius, you said that your daughter was turning 18 and you were most worried about what to give her. Did you resolve this issue in the end?

— You know, I was amazed. After that, dozens, almost a hundred suggestions started coming to me — what to give an 18-year-old girl for her birthday. From completely different Belarusians, whom, unfortunately, I don't even know. I am very, very grateful to them for that.

My daughter and I decided it would be a new phone. And, of course, what a girl needs, especially when she's 18 and when relationships with boys are starting, is cosmetics. I don't understand anything about that, she chose it herself.

— How widespread is actually the practice of "inflating" sentences under Article 411 (malicious disobedience to the demands of the correctional facility administration) within the system?

— Before I got behind bars, I had no idea of the scale of the tragedy with Article 411. It seemed to me that across the country there were two or three cases, and that it mainly concerned aggressive criminals who openly opposed the penitentiary system.

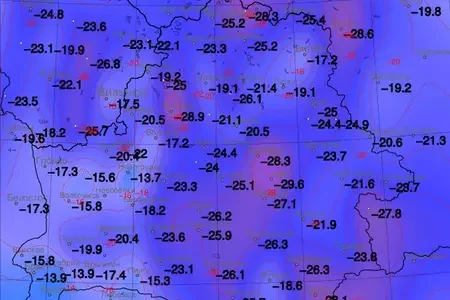

In fact, it has absolutely horrific dimensions and affects not only political but also criminal prisoners. This is real falsification. First, minor "violations" are recorded — an unbuttoned button, not greeting someone. Then they accumulate them. Or, as in Prison No. 8, a sick person did not do their morning exercises at the specified time. For this, they are declared a malicious violator of the regime and "tacked on" one and a half, or even almost two years under Article 411.

For example, in Žodzina Prison No. 8, under the prison regime, there are about 50-60 people — both political and non-political. Of these, in 2025 alone, nine people were prosecuted under Article 411. Nine — that's effectively every fourth or fifth person.

They are saddled with new violations, they remain in prison with a new sentence, and after transfer to a strict regime colony, they are "spun up" again. This conveyor belt is absolutely ceaseless. There are cases where people received Article 411 10-12 times, political prisoners can have five such episodes.

As a result, a person feels completely defenseless and desperate: the entire term turns into endless imprisonment. These are conditions of torture that very strongly break people.

Therefore, in the framework of negotiations, it is important not only to achieve the release of people but also to stop repression, so that new political prisoners do not appear, and also to abolish such perverse practices.

— You previously said that human rights defense has become stronger, but emigration complicates everything. What are the main difficulties and challenges now?

— We are not tired of the fact that all this does not stop. We will help all the time. This is our mission and our calling. Since the creation of "Viasna" in 1996 — soon 30 years — we have always operated under either large or small repressions and constantly defended and extracted people who are political prisoners. This was and remains the mission of our organization.

But the most difficult aspects of working abroad are, of course, being detached from reality. It is very important to remain in the real field, in the field of Belarusian needs. And here, the key is obtaining information from within the country.

Many people who could previously count on our help now remain defenseless, because in conditions of emigration, we practically cannot help them. And, of course, collecting information. We understand that the published list of political prisoners is incomplete, and we admit this. But not because we work poorly, but because it is extremely difficult to obtain this information.

Therefore, this gap between the country and us is one of the main challenges, especially when release procedures are underway, so that no one is forgotten.

— Many people are afraid to report about their relatives who are convicted under political articles.

— We have cases where people informed us about their relatives who are in places of deprivation of liberty and are undoubtedly political prisoners — there are no doubts about their status. But we cannot publicize and include these names in the lists, because it is an emphatic requirement of close relatives.

I believe that such a requirement is not very correct, as it creates difficulties in negotiation processes. If a name is not mentioned, the person can truly be forgotten. But we understand people and try to ensure that such names still appear in one form or another, including in exchange mechanisms.

— Do you have approximate estimates of how many political prisoners there might actually be in Belarus?

— I think that at least 200-300 people are not included in our official lists. At least.

"Don't despair"

— If you could address three audiences — those who remain behind bars, Belarusian society within the country, and international actors conducting negotiations — what would you say to each of them?

— To those who are currently behind bars, I would say: don't despair. Soon we will definitely embrace each other. The last time is always the hardest. You need to grit your teeth and most importantly — don't despair. Because I, as a person who was there, know that the worst state is the state of despair.

To those within the country, I would wish the same — just don't despair. Everything can change, and I very much hope that we will also embrace each other.

To the people conducting negotiations, I would also ask, understanding how difficult it is, because the negotiators on the other side are quite difficult — also not to despair and to continue, to continue talking. Because there is nothing more important than the fates and lives of people. There is absolutely nothing else that matters — neither sanctions nor other political motives — compared to our responsibility for the fates and lives of people who are currently behind bars.

Uladzimir Labkovich is 47 years old, a lawyer and human rights activist from "Viasna". He was detained on July 14, 2021, along with Ales Bialiatski and Valiantsin Stefanovich. On March 3, 2023, he received 7 years of imprisonment on charges including "financing group actions that grossly violate public order" and "smuggling". On December 13, 2025, Labkovich was released and forcibly removed from Belarus to Ukraine among 123 other political prisoners, after which he traveled to Lithuania.

Comments