"I emigrated when it wasn't yet mainstream." Darya Rakava wrote a book about Belarusians in emigration

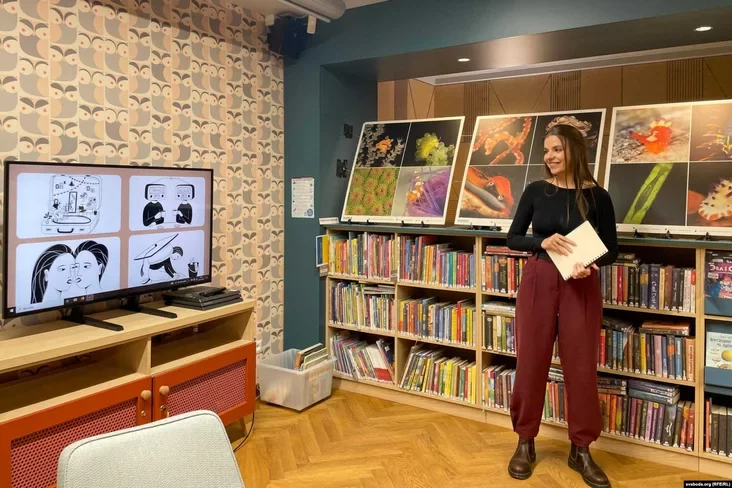

An interactive presentation of the heartfelt book "I/We Emigration," written by 25-year-old Belarusian and Polish language teacher Darya Rakava, took place in Warsaw, Radio Svaboda reports .

Darya Rakava found herself in Poland in 2018 – she wanted to get a European education. But in 11th grade, she hadn't yet decided what she wanted to do.

"I wanted to become an actress, but my dad told me that with such a profession, I'd live in a box. So we chose something after which people don't live in a box — political science... Staying in Belarus was not an option for me. I understood that with my sharp tongue and what I questioned in school, things wouldn't be very good for me in Belarus. My parents pushed me to study in Europe — they brought me to Lublin. So I emigrated when it wasn't yet mainstream," Darya recounts with humor.

However, in her book, she clarifies that "going somewhere" (as she did from Belarus to Poland in 2018) and "leaving somewhere" (as most current forced emigrants do) are different things. Such an experience is traumatic in any case.

Darya arrived in Poland with a B2 level of Polish (which is a fairly high level, above average. — RS). But, as it turned out, it wasn't enough for full communication. And language gives freedom, Darya asserts.

"In a new country of residence, you remain silent for a long time. First, you lack words. And often you hear from various people where you should go, how you are 'not like them,' and how awkward you are if you do decide to speak up. Discrimination becomes such a habitual part of life that by the time you have enough language to answer everyone, you continue to remain silent, having believed in your inferiority. You pay taxes, do useful work like locals, have good experience and several languages in your head, but still, you are 'superfluous' and live with it, shyly keeping your mouth shut," writes Darya Rakava, the author of the book "I/We Emigration."

"It accumulated and gathered"

Why did this book appear? When Darya started working as a Polish language teacher, her students told her about their adventures in a foreign country. She collected these emigration stories. Since she was a teacher, she analyzed everything, categorizing it. And she had plenty of her own adventures and observations.

The last straw for Darya was a visit to the local administration (urząd).

"It seemed to me then that I spoke Polish quite well, and I shouldn't have any problems. But the gentleman at the office decided that I didn't understand him very well and started translating some words into Russian. I didn't like that, and I decided to write a book about the difficulties of emigration. I wrote it quite quickly; within a few months, I already had the text. So, it had accumulated and gathered," the author recounts.

She wrote the book in Russian, although she is also perfectly fluent in Belarusian, — so that it would be useful to both Russian speakers and those who know Russian.

In the new publishing house RozUM Media, founded in May 2025 by Belarusian Pavel Lyahchylau, the book was released in two versions. In February, it will also be published in Polish.

From Confusion to Confidence

The presentation of the edition was interactive. Darya asked the audience what emigration meant to each of them — in one or two words. The answers varied widely: "a test," "24 hours a day madness," "new opportunities and perspectives," "crap," "before and after," "activation of fears," "changes and a new life," "independence," "struggle and difficulties," "rebooting oneself anew," "a mess," "crisis," "a strange wonder," "a new headache," "a forced measure"…

The author listened to all the options and summarized:

"The experiment succeeded. You can buy the book — it will definitely be about you!"

Darya described not only her own emigration story, though it is also in the book. The new edition features more stories and experiences of others — students, friends, neighbors.

"There are many of us, so confused, in a foreign land, and it doesn't depend on status or age. I show the path from the confusion of the first days to the confidence that at least I gained, and I think everyone will gain.

The book has many funny situations, and I use a lot of irony. I wanted you to laugh — to think that everything isn't so terrible," assures the author.

Darya's work contains 6 chapters, 33 illustrated stories about a new life in emigration and how to cope with difficulties. There are serious essays: about Polish police, bureaucratic hell, deportation, rapidly changing laws. There are touching texts about home and family, language, friendships in emigration, about bilingual children and teenagers.

"I even wrote about my romantic dates in Polish, about the beginning of the war, about sad holidays not spent with loved ones, about those who return, and about how 'the old world collapsed, and the new one hasn't been delivered yet'," says Darya.

The author promises: if someone doesn't find something in the first book — there will be a second.

"Don't Live a Deferred Life"

At the presentation, Darya read a fragment from the essay "I No Longer Want to Live Out of Suitcases," which, in her opinion, offers hope.

"I wasn't leaving Belarus. I was going to Poland. No matter how you look at it, it's a big difference, but I experienced the household crisis of an emigrant just as hard as those who left, fleeing repression and war…

Why do you need your books? You live in a dormitory. Should I bring you a keyboard too? — that's my mom.

She doesn't understand why I ask her to bring things that I will have great difficulty carrying with me with every new move. I just want my things to be with me. And to have something to put on the shelf. For many years, besides these books and a keyboard, I had nothing.

I ate from the cheapest IKEA plates and was content with dormitory bedding, and later with pillows and blankets from rented accommodation.

Five years later, I bought my own duvet, pillow, and also a large yellow armchair, a rug, a two-meter mirror, a desk, and many lamps.

My friends were shocked — not only because I moved approximately every six months, but also because my temporary residence permit could simply not be extended, and I would have to leave permanently. Why these things? Such a waste…

The first time I moved with all this furniture was just three months later. I had to find a van and pay for the relocation.

But in the new place, once I arranged the furniture, I immediately felt at home. Already on the first day. I didn't have to get used to it, because my furniture and my linen were with me. Beloved, cozy, chosen by me and arranged with my own hands.

I was so happy that the next day I bought a lot of beautiful dishes for myself: wine glasses — wide but on very thin stems, double-walled coffee cups, beautiful drinking glasses, two flower vases, handmade ceramic plates.

If I'm ever destined to leave, I'll just give it all away.

I knew I no longer wanted to deprive myself of this domestic luxury and live in a place I wouldn't even want to return to from work, just because they might not extend this silly residence permit.

What if I never get citizenship? Or my own apartment? Will I die without ever drinking wine from my beautiful glasses? I don't have money for my own housing and have slim chances of getting a passport, but I do have fifty zlotys for a glass.

And I also have a great desire not to live a deferred life," writes Darya Rakava, the author of the book "I/We Emigration."

Comments