"We are closer to Europe than you. And people have more weapons than the police." How Abkhazia lives under Russia's control

I have been to Abkhazia many times — my family lives here. I am familiar with every ruined house in Sukhumi, the pebble beaches, the roads where cows wander, and the mountains where Russian soldiers' shots are occasionally heard. I have seen the lives of people who have electricity for only two hours a day and no official documents at all. Despite the difficulties of life in the unrecognized republic, many Abkhazians cannot imagine moving away. And there are those who can no longer return home because of their social media posts. Familiar, isn't it? Local residents tell "Nasha Niva" in a special report what life is like today in the territories that Putin calls "liberated."

Black Sea coast, Abkhazia, summer 2022. Photo from the author's archive

Since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine and the closure of familiar tourist destinations, Belarusians have increasingly chosen Abkhazia for their holidays. Those who previously enjoyed the beaches of Odesa, Zatoka, and European resorts are forced to look for alternatives. Belarusian tour operators offer hotels in Gagra, Pitsunda, and Sukhumi, promising low prices, a clean Black Sea, mountains, and Caucasian hospitality. No visa is required, but getting there from Minsk will involve three transfers and take almost two days.

For security reasons, all names of the characters, except Daur Buava, have been changed.

Thirty-two years have passed since the end of the Georgian-Abkhazian war, but many of those who fled then have not returned home. Abkhazia remains in international isolation. Only Russia, Nicaragua, Nauru, Venezuela, and Syria recognize the region as an independent state, while the rest of the world considers Apsny (the name of Abkhazia in the Abkhaz language) an occupied part of Georgia.

Anyone who has been to Abkhazia will begin their story by describing its incredible nature, warm clean sea, and Caucasian hospitality. But they will most likely end it with stories of abandoned houses, of which there are many here.

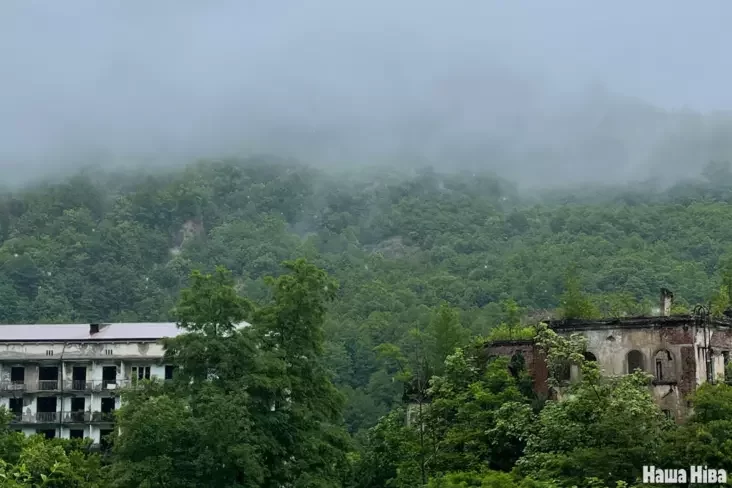

Sukhumi, Abkhazia, 2013. Photo from the author's archive

In Abkhazia, they are not considered ownerless. These are often Georgian, Armenian, or even Abkhazian homes of those who had to flee during the war. Neither local residents nor the state can occupy them. They remain empty for various reasons: some have not yet returned, some do not have money for repairs, and some have already died, but their children are not yet engaged in property restoration.

This is especially acutely felt in the ghost town â Tkvarchal (Tkuarchal). On August 14, 1992, a military conflict began between Georgia and Abkhazia, after which the city was heavily destroyed and practically depopulated. Georgians massively left their homes, and the population of Tkvarchal decreased from 21,000 to 4,500 people.

Tkvarchal (Tkuarchal). Photo from the author's archive

Tkvarchal (Tkuarchal). Photo from the author's archive

"The war has begun! Hooray, hooray! We won't go to school!"

Jansukh, Sukhumi, 46 years old

Jansukh remembers the day the war started as if it were today. He was 13. He and a neighbor boy were sitting on the balcony. A Georgian military helicopter hovered over the house, firing at Abkhazian positions with such a roar that the windowpanes almost shattered. "The war has begun! Hooray, hooray! We won't go to school!" â Jansukh recalls his emotions at the time.

When I told the parents of young Abkhazians about Belarusian schools, where priests, policemen, or officials regularly visit, my interlocutors were surprised and said that there was no such thing in Abkhazia. Propaganda meetings with children are not held. But there are plenty of participants in the so-called "SMO" (Special Military Operation). Almost every Abkhazian has already attended the funeral of a neighbor who decided to earn money in the war in Ukraine.

Today, in Abkhazian schools, the anthem is played on Mondays. To the delight of locals â it's the Abkhazian one. The national flag can often be seen on the streets, and the main holiday is Victory Day in the Georgian-Abkhazian war, which lasted 413 days. It is celebrated on September 30. On this day in 1993, Georgian troops retreated.

Window in a house someone occupied, Sukhumi, 2013. Photo from the author's archive

Jansukh says that from 1993 to 2008, Abkhazia provided for its own essential needs: fuel, food supplies, basic medicine, and the operation of law enforcement agencies.

In 2008, Russia recognized Abkhazia's independence and over the next 17 years transferred more than 150 billion Russian rubles (about $2 billion) for the needs of the republic. Most of this money went to Abkhazian salaries and pensions. Another part was invested in transport, infrastructure, energy, and industry. However, locals hardly see the results of these investments: there are almost no playgrounds, roads are broken, and Abkhazians go to Russia or Georgia for treatment. Earnings are also scarce.

"Work is not our forte at all," says Jansukh. "Some have small businesses, some work in tourism. But seasonal income is not enough for a family of four, so many look for additional sources of income. Mining is very common."

Crypto farms have become a big problem for the region. Because of them, in 2024, a massive emergency power outage occurred throughout the republic, after which electricity was supplied on a schedule for only 2-4 hours a day. Here, it has been considered normal for the past five years to have no electricity for several hours a day. The serious deficit is caused by the low water level in the Jvari reservoir on the Inguri River and limited electricity supply from Russia.

As reported by the Ministry of Energy of Abkhazia, in October 2025, the Ochamchira district was left without electricity from 10:00 to 16:00. And in November and December, partial outages for several hours a day affected all residents of the Black Sea coast â from Gali to Gagra.

Sukhumi, Abkhazia, 2022. Photo from the author's archive

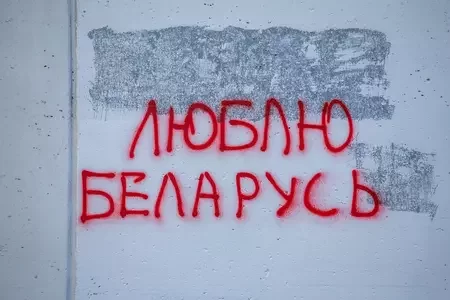

During my last visit to Sukhumi in 2022, I spent days walking around, looking at houses, inscriptions, and, of course, people. I remember a man with a cold, piercing gaze. I met him every day, wherever I went: to a cafe, to the gym, to the embankment, or to a restaurant. And then I saw him in the news: "On January 11, 2025, at 2:00 PM, a shootout occurred at the "Biskvit" cafe, resulting in a triple murder." That same stranger was shot dead.

"If you kill everyone you fight with, you won't have enough bullets," â Jansukh still remembers this paternal advice, which is why he doesn't carry a weapon. But if needed, he openly says, he will bring it in any quantity and anywhere.

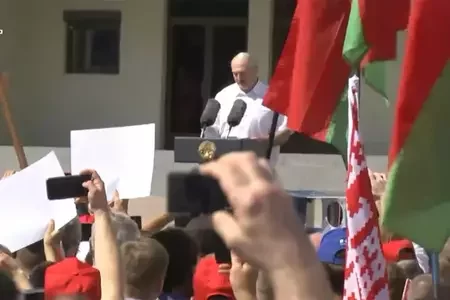

Many people in Abkhazia are armed, and this is a deterrent: people understand that any insult can end in a shootout. Perhaps because of this â and also because everyone knows each other â law enforcement officers in Abkhazia do not use weapons against their residents and do not even disperse protests.

"We are much closer to Europe than you are in this sense. And people have more weapons than the police," â my next interlocutor Murad reflects on the dispersal of Belarusian protests. However, in other respects, the situation is, of course, far from democracy.

A protesters' truck breaks through closed gates in front of the "parliament" building in Sukhumi. Protests erupted over an initiative to allow Russians to buy apartments in Abkhazia. Sukhumi, November 15, 2024. AP photo stock frame

"Our parties are formed not around ideas, but around surnames"

Murad, Sukhumi, 48 years old

Murad shares: their parties are formed not around ideas, but around surnames.

"Leonty Bzhaniya (fictional character. â NN) appears on the scene, hypothetically, and people follow him not because of a program, but because they know his family, consider it worthy, and trust it. Here, support is built on family reputation, not political promises," â Murad explains.

â I recalled a funny incident. In September 2004, to support Raul Khajimba, who was running for president, Oleg Gazmanov was invited to perform. He came out on stage and shouted into the microphone: "Adjara, I'm with you!" He probably drank too much chacha and didn't even check where he had arrived."

There are about 10 republics in the Caucasus, each comprising dozens of regions and autonomies. And given the number of Russian wars for territories since the collapse of the Soviet Union, it can be difficult for residents of other regions to distinguish between Ossetia, Alania, Abkhazia, and Adjara.

According to international law, Abkhazia is a part of Georgia occupied by Russia. Russia declares that Abkhazia is an independent state. However, the currency there is Russian, the country's phone code is +7, and there is no transport connection with any country in the world except Russia. Moreover, since 2010, about 4,000 Russian military personnel â soldiers of the 7th military base â have been permanently stationed in Abkhazia. And Russian channels broadcast propaganda.

"I categorically disagree with the term 'occupied territory'," â Murad states. â "Russians do not openly participate in the governance of our state. Although we are under their strong influence. But personally, I believe that Lukashenka and Putin are two scoundrels. One holds his people in slavery, and the other has completely lost his mind. If Lukashenka at least doesn't fight with anyone, then this one has gone completely insane. The war is a separate topic. I don't understand at all how Abkhazians, who themselves experienced a terrible war, can support, or even worse, go to fight in a foreign country."

Vladimir Putin shakes hands with "president" of Abkhazia Badra Gunba before talks in the Kremlin. Moscow, March 5, 2025. AP Photo Bank image

In 1992-1993, Abkhazians witnessed a terrible scene. Funerals took place every day. During the war, about 4,000 people died. For the Abkhazian ethnic group, numbering just over one hundred thousand, this was a real tragedy.

"It seems to me that the more people have the opportunity to see the world, the greater the likelihood that there will be no war," Murad believes.

After 2014, mainly Russians and Belarusians come to Abkhazia. Most often, they enter from the Russian side, through the Psou checkpoint, thereby effectively violating Georgia's state border. It is for this reason that you will not get a stamp in your Belarusian passport.

"For my sister to be able to visit us, I arranged a special invitation. She entered from the Georgian side: first she passed their control, then the Russian, and only then â ours. The last time, the Russians held her for questioning for almost an hour, but everything was polite and courteous. Although I am, of course, against having representatives of a third state at our border," â Murad says.

In the Caucasus, it is customary to care for all relatives, so I was very surprised when I heard that there is a nursing home in Abkhazia. But there are no locals there â elderly people from Russia, Greece, and other visitors live here. If an Abkhazian were placed in a nursing home, their family would never be cleared of shame. The same attitude applies to orphanages here: children from troubled families are sent there, but not Abkhazian ones.

The difference in attitude towards locals and tourists is felt everywhere. You walk through the market and notice that peaches that just cost 100 Russian rubles (1.2 dollars) suddenly become 200 for you.

My acquaintance, who has lived in Abkhazia for almost 20 years, constantly faces everyday discrimination. There was an instance when she came with her children to the monkey park, where admission is free for Abkhazians under 14. At the ticket office, the employee demanded payment, and after hearing the surname, accused the woman of lying. Only when her Abkhazian husband approached did the employee apologize for the "misunderstanding."

The exception is deep mourning: "As long as you are in a closed black blouse and a long black skirt â you are considered one of their own here by everyone."

Market stalls, Pitsunda, 2022. Supermarket in Sukhumi, 2022. Photo from the author's archive

"In Abkhazia, the respectful attitude towards pregnant women and children is impressive. But I gave birth twice not here"

Karina, 38 years old, moved to Abkhazia from Russia in 2008

"In Abkhazia, doctors have increased responsibility: if something goes wrong, the patient's family will come to sort things out. All medical workers understand this," explains Karina. "Officially, medicine here is free, but in practice, everyone tries to leave what they can â for a regular appointment, for an IV drip, and for childbirth."

Karina says that many families still hold archaic beliefs about diseases and treatment. For example, mental disorders are considered sacred here and are accompanied by rituals. Strict prohibitions are associated with chickenpox and measles: if someone in the family falls ill, men are not allowed to shave, hunt, kill animals (even insects in the house), attend funerals, or have sex for 40 days. And some light candles daily or cook ritual porridge.

"I like living in Abkhazia. The respectful attitude towards pregnant women and children is especially impressive. But I gave birth twice not here. Why did I choose to give birth in Russia? Because I wanted my children to have Russian citizenship. Abkhazia is an unrecognized state, and I want to provide them with a normal future, I want them to be able to enter a university in Russia later."

Abkhazia's unrecognized status limits its residents' basic opportunities. Their passport is recognized almost nowhere, which means people cannot freely travel to study or work anywhere except Russia. Yet when I ask Jansukh if he could at least get a Georgian passport for convenience, he doesn't even let me finish: "No way. That's an insult. Why would I need a passport from a hostile state?"

Local residents of Sukhumi on the embankment, summer 2022. Photo from the author's archive

"Even in childhood, I felt immense tension between our peoples. At that time, Georgians wouldn't sell cars to Abkhazians, even if they offered more money. They wouldn't register houses to Abkhazians â we had to ask relatives from Tbilisi to help with documents. And even today I think how lucky we were to get rid of them back then, otherwise they would have devoured us here like locusts," â Jansukh is convinced.

Abkhazians and Georgians differ in language, origin, and mentality. Some cultural traditions that have formed under the influence of close neighborhood remain common.

"I believe Georgians are wonderful people. But they have one drawback â nationalism. They can do a lot of good for you, and then tell you that you're sh** just because you're not Georgian," â Jansukh explains.

I often heard stories from Abkhazians that during Soviet times, Georgians universally suppressed their language. Signs were in Georgian, television was in Georgian, education was in Georgian. Thirty-two years have passed since a single Georgian cannot utter a word in the self-declared republic, but the problem of the Abkhazian language has not been resolved.

In kindergartens, there are Russian and Abkhazian groups, and educators speak to children in both languages. There are fewer children in Abkhazian groups â as there are fewer native speakers in general. In Abkhazian schools, instruction in the native language is available only up to the 4th grade, and beyond that â about three hours a week for language and literature.

The history of Abkhazia, condensed into a 320-page textbook for all students from 5th to 9th grade, is in Russian. The constitution is written in Russian, court proceedings are in Russian. In theaters, restaurant menus, government institutions â the Abkhazian language is almost not used here either.

Another feature of life in the unrecognized republic is the absence of international postal services and global transport companies. There are no familiar mass-market stores here either: no Zara, no H&M, no Adidas. Most often, locals use the Russian marketplace "Wildberries." Delivery can only be arranged to Adler in the suburbs of Sochi, and from there, you have to pick it up yourself. However, Sukhumi supermarkets have many Belarusian products: dairy from "Brest-Litovsk" and "Savushkin," "Minsk sausages," and even sweets from "Kommunarka."

"I want Ukraine to exist, but a small one"

Jansukh, Sukhumi, 46 years old

When the conflict around South Ossetia escalated into hostilities in August 2008, Jansukh went there to fight on Russia's side. He says he went for Abkhazia, wanting to settle old scores from the Georgian-Abkhazian war.

Ossetian fighters entering Tskhinvali against the backdrop of a portrait of Vladimir Putin. South Ossetia, August 2008. During a brief war, Russia established control over the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Photo: AP

â You know, I often listen to Radio "Sputnik," and all the military experts, Russian propagandists there, don't understand why their army fights so toothlessly. They believe that much more significant strikes should be inflicted on Ukraine so that it loses its statehood entirely.

â Well, what do you think about that ? Do you want Ukraine not to exist ?

â I want it to exist, but as a very small country that can never threaten anyone again.

â Who did Ukraine threaten ?

â Well, are we going to talk about that now, or about Abkhazia?

Unlike Belarusian channels, Jansukh has not encountered war propaganda on Abkhazian television. But on Russian channels, which are available in every home, it happens constantly.

"People believe everything they see on TV"

Dinara, 40 years old, moved from Ukraine in 1999

"In fact, people here, due to their lack of education and narrow-mindedness, believe everything they see on TV. And propaganda works well here. That's why most people love, adore, and are ready to pray to Putin. But my family and I are categorically against it. By the way, I also know a lot about your Belarusian protests â I followed on YouTube how everything unfolded there. I'm interested in politics, so I'm categorically against war and old tyrants â Lukashenka and Putin," â Dinara shares.

She recalls that before 2008, the standard of living in Abkhazia was low, and the crime rate, conversely, was high. There was no work, and overall, a sense of disarray was palpable everywhere. The Sukhumi embankment was full of potholes and unlit. After Russia recognized Abkhazia and took control, something slowly began to be rebuilt.

Sukhumi embankment, summer 2022. Photo from the author's archive

"Of course, there are things in Abkhazia that I am not happy with. But if I compare it to Russia, I wouldn't live there. There are many reasons. I don't like Russia; it's an aggressor country. I don't like the people who live there. Especially now, when everything in the world is being blocked there. Here, both Instagram and YouTube work. And I can, in principle, express my opinion. For now, at least," Dinara adds.

However, this does not apply to everyone. On May 19, 2022, Abkhazian special services opened a criminal case under the article "state treason" against Daur Buava, a native of Tkvarchal (the same ghost town). He now lives in Georgia.

"If I go to Abkhazia now, they will give me a show trial there"

Daur Buava, 30 years old, Tkvarchal â Tbilisi

"Until 2021, I lived in Abkhazia and recorded videos about religion â for example, comparing Islam and Christianity. One day, I accidentally stumbled upon a TikTok live stream where Abkhazians and Georgians were cursing and arguing about who was whose enemy. At that time, I was just an observer: I approached everything calmly and with interest, didn't try to offend anyone, and merely expressed my position. But the words of one blogger struck me, and I decided to go to Georgia and talk to him in person. Already on the evening of my arrival, I was welcomed into the home of those I had considered enemies my whole life," â Daur recalls.

Daur Buava. Photo from the "Amra" organization's Instagram

He says that for many years he was convinced: "Georgian children are taught from birth that Abkhazians are enemies and must be exterminated. I thought so because I only had one source of information (Russian television. â NN)."

After living in Tbilisi for a month, Daur realized that there was no hostility towards him as an Abkhazian in Georgia. On the contrary, people reacted warmly, asked how they could help, and called him "brother."

"I thought that our Abkhazian perception of Georgians as enemies was greatly exaggerated. I posted a video with these thoughts online â and went to sleep. In the morning, I woke up famous," â Daur says.

A few days later, on Abkhazia's main TV channel, security service chief Robert Kiut declared Daur a wanted man.

"They branded me with labels â I was an enemy of the people and a traitor. I was in shock. But when I re-evaluated all this, I became convinced that I had done everything correctly. They want to shut me up, imprison me, and hide the truth from others. It's not profitable for them for our people to know that Georgia is ready to help," he believes.

Daur notes that in Georgia, Abkhazians are provided with free education, medicine, assistance, and temporary housing for refugees.

"Approximately two years ago, a lawyer called me and said that as soon as I returned, the trial would immediately begin. I suggested holding the session via teleconference, but the lawyer simply said that even with complete innocence, such a case is impossible to win. I was advised to come, apologize, and 'atone for my guilt' by serving alongside the so-called 'our guys in the "SMO,"'" â Daur recounts. â "I would understand if Ukraine attacked us. But why should I take up arms for someone else's interests? We live in the Caucasus."

Daur states that today in Abkhazia, Russia decides everything. He believes that the authorities pursue a policy aimed at preventing Abkhazian youth from contacting Georgians.

"The previous so-called president and the current manager of the republic have both stated this. It got to the point where State Security Service (SSS) officers came to a guy who was showing Abkhazia to a Georgian on a live broadcast and forced him to apologize on camera. There was another incident â an acquaintance posted on his Telegram channel with the message, 'Why are we going to Ukraine to fight for Russia's interests?' The next day, FSB agents arrived and took him to Moscow. Where he is now is still unknown," â Daur says.

Daur Buava now lives in Tbilisi; he is married to a Georgian woman, writes a book, and is involved in activism. Together with the Georgian Mikhail Kvatashidze, he founded the organization "Amra," which means "sun" in Abkhazian. In streams and podcasts, they talk about the opportunities that the free world offers. They call on the youth of Abkhazia and Georgia to unite and fight against a common enemy â Russian propaganda.

Mikheil Kvatashidze and Daur Buava near the European Parliament in Belgium. Photo from the "Amra" organization's Instagram

The last question I ask Daur is the same one that thousands of Belarusians have been asking each other for the past five years.

â Do you think you will ever return home?

â I will return. I will definitely return.

Working in Poland or Lithuania? Support "Nasha Niva" — it's completely free for you, and we will be able to do more for Belarus and Belarusian culture!

Working in Poland or Lithuania? Support "Nasha Niva" — it's completely free for you, and we will be able to do more for Belarus and Belarusian culture!

Rheinmetall proposes to prepare hundreds of modular hydrogen fuel production plants. They could be a lifeline in the event of a severe war with Russia

Rheinmetall proposes to prepare hundreds of modular hydrogen fuel production plants. They could be a lifeline in the event of a severe war with Russia

"Do you want your legs to give out, like Ihnatovich's?" Losik recounted how he crossed paths in prison with those convicted of Dzmitry Zavadsky's murder.

Comments