Belarusian historian Viachaslau Nasevich explained how paleogenetics data allowed scientists to better understand the history of the region.

Paleogenetics provides answers about the origin of peoples. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

For a long time, historians were forced to wander in the dark, relying on legends about Roman origin — for example, the famous myth of Palemon — or on shaky linguistic theories. In the 19th-20th centuries, scientists noticed similarities in the names of rivers and other hydronyms in Lithuania and vast areas of modern Belarus and Russia.

Thus, a popular concept about the vast territory of ancient Baltic settlement was born.

Modern science has acquired a tool that mercilessly destroys some romantic myths and confirms other theories — paleogenetics. Belarusian historian Viachaslau Nasevich explained how new data forces a completely different look at the history of the region.

The End of the Era of "Hydronymic Imperialism"

The history of the origin of peoples has always been a field for myth-making. Initially, people believed in legends like the origin of Lithuanians from the Roman Palemon; later, they sought roots in Sarmatians or Gepids. In the 20th century, linguistics replaced legends.

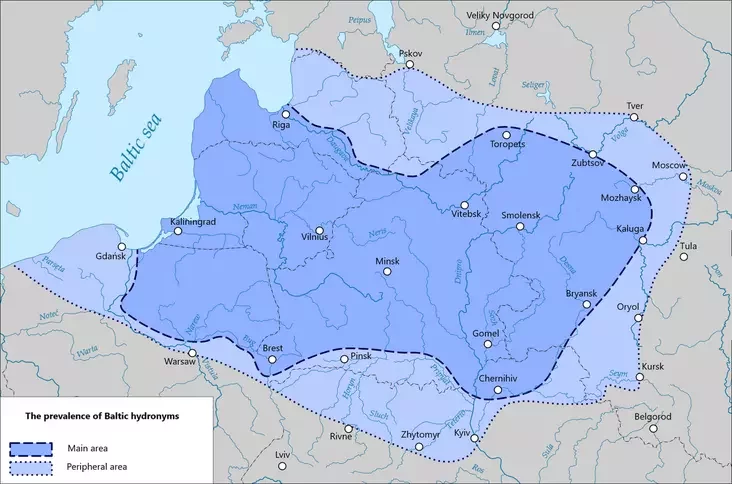

Map of the prevalence of Baltic hydronyms. But it should be understood that on the territory of Belarus, these are isolated inclusions, not total coverage. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

One of the most persistent myths claims that the map of Belarus is covered by a "solid carpet" of Baltic hydronyms.

Scientists noticed similarities in hydronyms (i.e., names of rivers and lakes) in Lithuania and vast areas of Eastern Europe — across all of Belarus, Smolensk region, Bryansk region, all the way to Moscow and even further east. Academicians Vladimir Toporov and Oleg Trubachev created an influential theory that these names were left by the ancestors of modern Balts, who once occupied this entire area.

"This idea transformed into a myth that was picked up without much understanding. Today, some radical figures call the creation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania a 'Lithuanian Reconquista' — claiming that it all once belonged to us, was taken from us, and we were just taking back what was ours. But this is a myth," asserts Viachaslau Nasevich.

The problem with linguistics is that river names cannot be precisely dated. A hydronym considered Baltic, for example, Menka, could have been borrowed by incoming populations from older inhabitants whose language is completely unknown to us.

However, Viachaslau Nasevich personally analyzed a list of two thousand rivers and streams in our territory and came to a conclusion that might upset proponents of the "great Baltic homeland" theory.

It turned out that if all water bodies are considered, the truly dense array is formed not by mysterious ancient names, but by transparent and late Slavic ones — various Kamenkas, Sasnouskas, and Alkhovkas. It is these that form the main background, among which nominally Baltic roots are only isolated inclusions, and by no means total coverage.

Moreover, the historian debunks the notion that a river's name is something eternal: hydronyms change along with the language of the population. As proof, he cites the Pronya River, a major tributary of the Sozh in the Mogilev region, which in 16th-century documents still appeared under the purely Slavic name Propasć.

Why Skulls and Pots Are No Longer an Argument

When linguistics failed to provide precise answers, scientists turned to archaeology and anthropology. But here too, two irreconcilable schools existed. "Migrationists" claimed that changes in pot patterns signified the arrival of a new people.

"Autochthonists" countered: "Pots travel, not people," meaning that the population remained the same, only fashion changed.

Anthropometric study of skulls is not reliable, as seen in the example of actresses Keira Knightley and Natalie Portman, who resemble sisters but have completely different origins.

Skull measurement — craniometry — also proved an unreliable method for determining kinship. Nasevich gives a striking example: actresses Natalie Portman and Keira Knightley resemble sisters but have completely different origins — Jewish and Celtic, respectively. External resemblance is deceptive.

For a long time, science simply lacked the tools to look deeper. A revolution occurred when scientists learned to extract DNA from ancient bones and teeth. The Y-chromosome, which is passed from father to son almost unchanged, is of particular value. This allows tracing the lineage of entire populations thousands of years back.

The geneticists' conclusion is unequivocal: practically any change in archaeological culture was accompanied by the arrival of new people.

The autochthonous theory that people stayed in one place since the Stone Age collapsed.

Mysteries of Lithuanian Blood

Paleogenetics has painted a complex and multi-layered picture of the settlement of our region, which completely refutes the theory of "eternal stagnation."

Prevalence of the Corded Ware culture (Battle Axe culture), which brought with it haplogroup R1a. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Initially, these lands were inhabited by Neolithic forest hunters, but in the Bronze Age, the situation changed dramatically. From the south, from the shores of the Black Sea and the Dnieper basin, came a powerful wave of migrants — bearers of the Corded Ware culture (Battle Axe culture) and haplogroup R1a. It was they who brought Indo-European languages here and mixed with the ancient hunters.

The most interesting, even sensational, discovery concerns the origin of those whom we are accustomed to considering ancestors of the Balts: their roots, as it turned out, extend far to the East.

It turned out that a significant part of the genetic code of modern Balts came from Trans-Urals and Western Siberia. Bearers of haplogroup N migrated through Estonia approximately in the 8th-7th centuries BCE.

Here lies the most interesting detail. Among representatives of the East Lithuanian barrow culture of the 1st-5th centuries CE, who are direct ancestors of Lithuanians, the concentration of this "Uralic" haplogroup N reached 70%. However, in modern Lithuanians, it is only about 40%.

"It's like with alcohol: to get 40-degree vodka from 90 degrees, you need to add water. To reduce the concentration of a haplogroup from 70% to 40%, the ancient population had to mix with someone else by about half.

This means that the population of Lithuania during the Roman Empire was not yet entirely modern Lithuanians," explains Nasevich.

This refutes the popular thesis in Lithuania that the local population lived unchanged and untouched for millennia. In fact, the gene pool was constantly "diluted" by newcomers.

Navahrudak, old castle. Photo: Nasha Niva

When Did the Paths of Belarusians and Lithuanians Diverge?

Genetic studies show, according to Nasevich, that even a thousand and a half years ago, it was almost impossible to genetically distinguish the ancestors of Balts and Slavs. Probably, there was some common population. The difference arose due to different migratory vectors.

"Early Slavs, who, according to archaeological data, formed in Polesia (Prague culture), were very similar to early Balts. So similar that, perhaps, even indistinguishable," asserts Viachaslau Nasevich.

Part of the early Slavs moved from their Polesian homeland southwards over and beyond the Danube, where they became part of the Avar Khaganate and mixed with the local population. When the Khaganate began to disintegrate, some of these "new Slavs" returned from beyond the Danube back north, to the territory of modern Belarus and Ukraine, bringing the "Dinaric" haplogroup I2, which is the main genetic marker distinguishing Belarusians from Lithuanians. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The separation occurred later, due to different directions of migration. The ancestors of Lithuanians moved north, where they mixed with the local population.

But the ancestors of the Slavs chose a different vector — southwards. Part of this common population moved to the Danube, where they became part of the Avar Khaganate.

The Avars, unlike the northern tribes, did not cremate their dead but buried them in the ground. This provided scientists with rich material: thousands of paleogenomes from the territory of modern Hungary.

"The Avars themselves, with Mongolian features, are clearly visible there. But there are others — those who share common features with the ancient population of Eastern Europe. These are the early Slavs. While in the Avar Khaganate, they actively mixed with the local Balkan and Danubian population," the historian recounts.

When the Khaganate began to disintegrate, some of these "new Slavs" from beyond the Danube returned north, to the territory of modern Belarus and Ukraine. They brought with them not only a new culture but also a new haplogroup I2 (Dinaric).

It is this "southern component" that today is the main genetic marker distinguishing Belarusians from Lithuanians:

- Among Lithuanians, there is a high percentage of haplogroup N (~40%) and an almost complete absence of "southern" I2 (~2%).

- Among Belarusians, the proportion of "Uralic" N is significantly smaller (10-15%, although in the Vitebsk region it reaches 20%), but there is a significant proportion of "southern" I2 (about 20%, and in Polesia — up to 40%).

Thus, Belarusians are a genetic mix in which local Balto-Slavic roots combined with a powerful influx of blood from southern Europe.

"Slavicized Balts" or an Independent Ethnos?

Genetic data cast doubt on the theory popular in some circles that Belarusians are simply Balts who switched to the Slavic language.

"Slavicization is not just a change of language. It was a physical arrival of people who returned from the south already in a mixed form. It is this influx of new population that formed the gene pool we have today and which distinguishes us from our neighbors," emphasizes Nasevich.

The modern gene pool of Belarusians and Lithuanians finally formed approximately in the 16th-17th centuries, when the population mixed within the borders of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

An interesting point concerns historical Lithuania — Vilenshchyna. It was there, according to genetic data, that the population with the maximum concentration of that same "Uralic" haplogroup N lived. However, over time, as Nasevich notes, this population mixed with the inhabitants of neighboring Menshchyna and switched to the language we now call Belarusian. This explains why among Belarusians of the north and west of the country, the percentage of the "Lithuanian" haplogroup is higher than in Polesia.

Kernavė, hillforts. Photo: Nasha Niva

Language and Blood — No Connection

Viachaslau Nasevich warns against equating genes with national identity. History shows that some peoples change languages more easily.

If 40% of the ancestors of modern Lithuanians were incoming bearers of other haplogroups, it means that at some point they renounced their former language and switched to Lithuanian.

The main conclusion drawn by the historian: pure peoples do not exist. We are all the result of centuries of mixing. Identity is not a set of chromosomes, but a matter of personal choice.

"What unites us is not that we have some common ancestors and others have different ones. We all have the same haplogroups, just in different proportions. Our ancestors changed their language and self-awareness more than once. This means that our choice is not predetermined by blood. It is not genes that define who we are, but we ourselves," concludes Viachaslau Nasevich.

«Nasha Niva» — the bastion of Belarus

SUPPORT USNow reading

Halina Dzerbysh told the prosecutor: "When I die, I will come to all of you at night." And life has already caught up with her judge and witnesses. The story of a pensioner who was given 20 years in a penal colony

Halina Dzerbysh told the prosecutor: "When I die, I will come to all of you at night." And life has already caught up with her judge and witnesses. The story of a pensioner who was given 20 years in a penal colony

«I just don't understand, who was the nuclear power plant built for?» No topic has caused such emotions for a long time as the power outage at Lukashenka's command

Comments