"Couldn't speak locally, and in Belarusian it was 'don't show off'." Vasil Siomuha's daughter tells how she was immersed in a sea of multilingualism since childhood

Alesya Siomuha, daughter of translator Vasil Siomuha and goddaughter of writer Uladzimir Karatkevich, grew up surrounded by the sounds of different languages, finally switched to Belarusian thanks to "Talaka" members, has lived in the USA for a long time, and preserves her Belarusian identity. "Mova Homiel" asked Alesya Siomuha about her childhood, her father's influence, and the presence of the Belarusian language in her daily life.

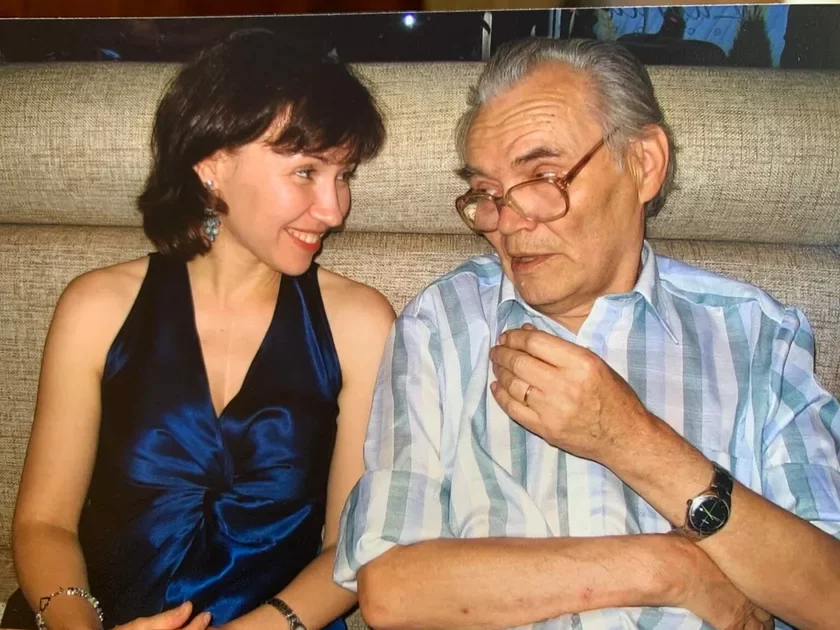

Alesya Siomuha with her father Vasil Siomuha. Photo from private archive

Vasil Siomuha (January 18, 1936 — February 3, 2019) was a Belarusian translator from German, Polish, Spanish, Ukrainian, Latvian, and other languages. One of his fundamental works is the complete translation of the Bible into Belarusian, which he worked on for 14 years.

Childhood and the sounds of different languages

— Alesya, your father, Vasil Siomuha, came from Pruzhany region, Brest Voblast, but you yourself were born in Minsk?

— Yes, I was born in Minsk, in Kamarouka, and my father came from Pruzhany region; he was born and grew up on the Yasenets farm.

— The question of language is interesting. What was your first language: Russian or Belarusian, and if Russian, at what point in your life did the Belarusian language appear?

— My father spoke different languages at home; he could switch from one language to another. My mother spoke Russian, and in the kindergarten where I was sent, everything was also in Russian. But my father often spoke in his own way, as he called it, in the Polesian dialect. He often told various fairy tales that his grandmother Repina once told him, and he retold them. He always told the same ones to me and my brother, about a sparrow or something else. The Polesian language was always heard, and my father also often spoke Belarusian.

He was constantly working, and when he worked, that's how he spoke. In the kitchen, or just passing by, he spoke Belarusian. When we were in the city or in more public places, like a store, he spoke Russian; with my mother, both Russian and Belarusian. My mother also often answered in Belarusian; she herself was from Homiel region.

In my childhood, I really didn't like riding buses with him, because when he was with me on the bus, he liked to "show me off": he would start talking to me very loudly, not in Belarusian, but in "trasianka" (a mix of Russian and Belarusian), a very vivid "trasianka", and often he would say such absurd things (Alesya laughs)… Everyone would start looking, and he would say something silly, like some "bot" from a remote village: "Daughter, look at that…", and as a child, I was somehow ashamed, but he really enjoyed it. Those were his jokes. It was his entertainment.

— So, he got such pleasure from it…

— He always got great pleasure from the "flavor" of language. He always enjoyed, first of all, seeing how people reacted to language, not only Belarusian, but also "trasianka", Polesian, and from time to time he would start speaking German with me.

When I was little, my parents later told me, he once tried to teach me to speak German and for about four months, he only spoke German at home. I don't remember this, and I don't know German. But I remember the sound of German, because he often spoke German at home, recited something, and then in Belarusian. Apparently, he had a very strong auditory perception of language.

He also needed music. He very often played classical German music and translated to it, reciting something from time to time. When translating from Polish, he would walk around the house and constantly speak Polish.

At school, I, of course, studied in Russian; I spoke Russian with friends, like all children at school. With him, sometimes in Russian, sometimes in Belarusian. I couldn't speak Polesian; I didn't know the Polesian language, except for those fairy tales he constantly told me. And when we came to Pruzhany, to Pruzhana, as he called it, I spoke Russian there, because I couldn't speak locally, and if you spoke Belarusian there, people would look at you like "don't show off," as if you were too smart.

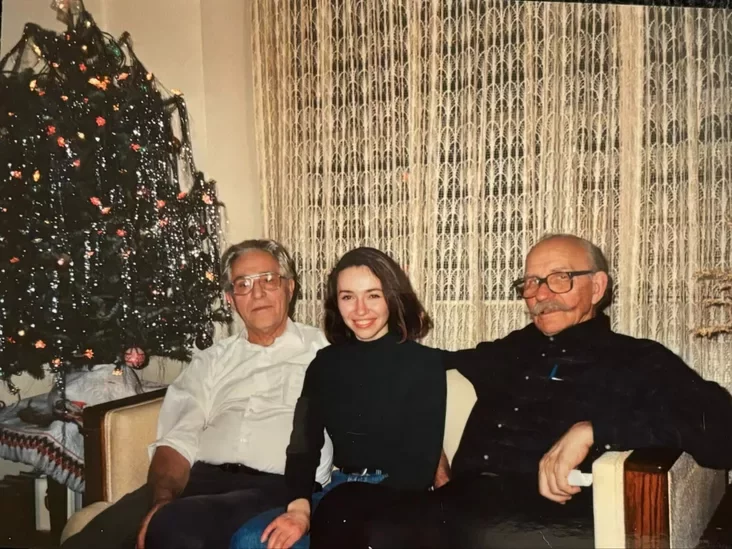

Alesya Siomuha with her father Vasil Siomuha and husband Mark, also Ales Kamotski and Ryhor Baradulin. Photo taken in Minsk in 2001 by Siarhei Shapran

The language situations were different. In middle school, everything was in Russian, so I don't even remember well how I spoke with my father then. Probably in Russian out of habit. In high school, I definitely spoke Russian with him, and he often switched to a formal, televised Russian.

It always sounded very correct from his lips, but somehow… inappropriate. I never knew if he was making fun of me or what. He seemed to say everything correctly, but my ears were always tuned to some trick. I had the impression that there was something behind it.

— Did you go to Homiel region to visit your grandparents?

— All my grandfathers died during the war, and my grandmother from Pruzhany region also died. We visited my father's aunt who raised him. My mother's mother lived in Homiel; I also visited her, but I don't remember what language she spoke with me. Probably Russian.

She worked, and I ran around with the children from morning till night, having complete freedom. She lived on Piasochnaya Street, I think that's what it was called. Everyone had gardens there, apple trees, cherry trees. But I remember that my grandmother spoke some kind of Belarusian-Yiddish "trasianka" with her friends. It was a local "trasianka". I partly understood what they were saying; there were many Belarusian words, especially when the topic concerned us.

There was a whole street of old people living there, private houses without sewage, with gas cylinders, water from a well. They sat on benches and "chatted away". Everyone was old, and grandchildren came to visit everyone. I called them grandmothers, but they were probably maybe my age now, but they seemed old to me then.

Everyone had vegetable gardens; there were a few Roma houses. The Roma spoke their own language. And my grandmother with her friends spoke this Belarusian-Yiddish "trasianka", but only with some of them.

— So, you could say you heard different languages from childhood?

— Yes. And from trips to Pruzhany, to Biaroza, to Sialec, to Homiel, at home. The sounds of different languages were always present. Sometimes my father played German operas; German was often heard, but it somehow didn't stick to me. At school, I studied English, so English was added too.

Student years and switching to Belarusian

— I understand that your Belarusian language came in your student years?

— Yes, I enrolled in the Belarusian philology faculty, met Maryna Miśko there, and, it seems, we were just taking entrance exams when I noticed that she constantly spoke Belarusian, as they say, without reason. It hadn't even occurred to me before to speak Belarusian all the time. But when I heard it from her, I thought it was interesting.

She invited me to a few "Talaka" events, and I went to see. Philology students spoke Russian among themselves, including those from the Belarusian philology department. Only some spoke Belarusian all the time, Maryna Miśko, Slavomir Adamovich, who was in the same year as me, Mikhaś Skobla, his wife also, and a couple of other people. But out of 110 people in the department, maybe seven or eight spoke Belarusian all the time. So for me, that was a turning point.

I attended several "Talaka" celebrations, saw other people who spoke Belarusian all the time. Ales Susha invited me for a walk and talk; we walked for two hours around Minsk, he constantly talked, persuaded me, and I thought, well, young people speak Belarusian all the time without reason, so I'll start too. And I did. I was 18 years old, and since then, I haven't used the Russian language.

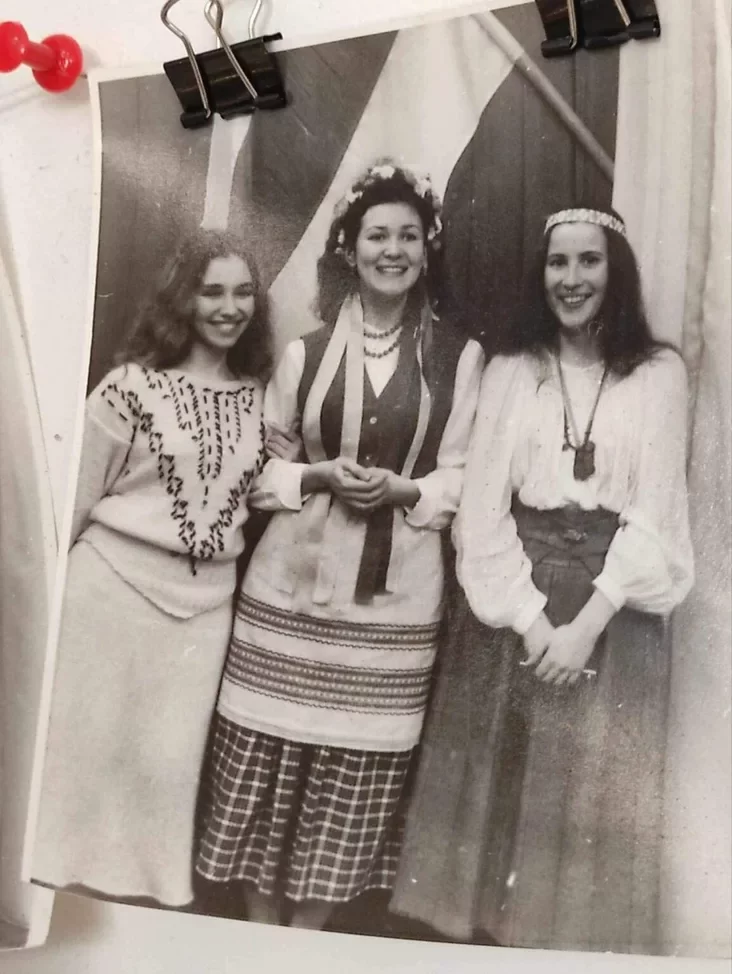

Alesya Siomuha (left) with two girls. The photo is kept in the Lutskevich Museum in Vilnius

— How did your father react when you switched to Belarusian, was there any reaction from his side?

— Very positive. He strongly supported my connections with the "Talaka" members, even priding himself that he hadn't raised his daughter for nothing. He strongly supported my first attempts at translation; I translated some things into Belarusian. The story "Kingdom Belarus", the story "Taboo" from Polish, I did a translation from English.

He said I was doing very well. But I felt that I didn't have the same endurance as him to sit day and night translating. I am not an academic type of person; I need action. I can translate something short, and then I need to do something else; I like variety and activity in my work.

But my father, I remember, was always at his desk. We would wake up, he was already up; we would go to sleep, he was still working. I didn't have that ability to sit at a desk. But you don't have to be a translator.

My father gave me language advice. I had a city vocabulary. When my father was growing up, everyone spoke his language; he was influenced by various people, which formed a broader linguistic base for him. My base is my father, "Talaka" friends, and what I read myself. But it's not a language passed down from a community, not a language of everyday situations. So he gave me advice on how they spoke, or how one should speak. This expanded my vocabulary.

I was already starting to get into journalism. We also traveled to Bialystok, it was very interesting to hear the Belarusian language of Bialystok residents.

Group photo in Yuri Turonak's apartment in Poland, approximately 1989-1990

Memories of Karatkevich

— Did the personality of Uladzimir Karatkevich, who was your godfather, somehow present itself in your life, influence your life?

— I hardly remember him personally. I remember one time, when he was at our house, he was swinging me on his leg and laughing. Swinging and laughing, and laughing so loudly that I remembered it.

As for his presence… I know that he baptized me and that he and my parents always met. My parents first lived in a barracks in Kamarouka, where I was born. Karatkevich constantly came there; he and my parents had their literary talks, drank a shot. And in 1970, we moved to a regular two-room apartment; Karatkevich visited there, but rarely by then.

I also remember when I was in kindergarten and my mother worked there, someone came and my mother talked to that person for a very long time through the fence. My mother later said that Valodzya came to say goodbye, knowing that the end had come, wanted to apologize and say goodbye. This was when he was already very ill.

But my parents always talked about him. He was in our house even without his physical presence. "Oh, Valodzya…", they recalled something, laughed. And my father always told me, "Well, your godfather, if he were alive, he would give you a good smack for such things."

Life in the USA and Belarusian presence

— How easy or difficult is it now, living in the USA, in a completely different linguistic and civilizational space where everything functions differently, to preserve your Belarusian presence and the Belarusian language?

— At first, I was in very close contact with Belarusians in New York, and the Belarusian language lived freely there. You could say that every Sunday after church, people gathered. Plus holidays. I immediately got to know everyone; the Andrusyshyn family was wonderful, such sincere, open, hospitable people. We traveled for holidays to New Jersey, where Vitaut Kipiel and others lived, to the Krachewski Foundation. That older emigration very strongly upheld the Belarusian community. It was a very strong community.

New York, 1993, Danchyk's apartment. In the photo, Alesya Siomuha with Danchyk's father — Paval Andrusyshyn and Anton Shukialoyts

And then I got married and moved to Washington. There was no large Belarusian community there. I met Alesya Kipiel, and we met from time to time. In Washington, together with Alesya, we created the Washington Circle of BAZA, the Belarusian-American Association. There were about 10-20 of us. The community still exists. I am the treasurer. We organize cultural events and promote Belarusian interests in American government institutions.

I lived and live near Washington. The emigrants here are different. These were mainly professionals who came for diplomatic, business, or educational matters, and everyone was very busy.

But I never had a question of preserving Belarusian identity. Where would it go? In that sense, there is no particular issue; it's impossible to forget it. There were no difficulties in preserving it, but there were no longer such opportunities to actively maintain it. But the community grew. Now there are many Belarusians here, and the Belarusian community is quite large.

Alesya Siomuha at work, 2023

"Veselka" cafe in New York on Manhattan, 2024. Alesya Siomuha with her childhood friend Maryana, the only person with whom she occasionally speaks Russian out of childhood habit

But American culture is different; it's different in the sense that the living environment is not the same, people socialize differently, relationships between men and women are different.

In the Belarusian environment, people believe they must know everything about everyone; here, it's a more individualistic culture. No one just barges into your house. This is a natural culture, but for Belarusians, it is often too formalized.

It took me a few years to understand this difference, and I have no problems, although over the years I have become more Americanized. My husband is American, my work environment is also American, and American culture dominates. So now it is closer and more comfortable for me.

I love my boundaries. I am quite an open person, but I define the limits of my participation, openness, or involvement myself; I don't like familiarity. I prefer autonomy; I realized that I always liked it. I was always independent in thought, and when an entire system is built on this, you immediately feel that it's to your liking.

I think my father would have liked this too. He was very individualistic, didn't like it when people intruded into his life without his permission. With close friends, he could allow himself more, but not with other people. He defended his boundaries, the boundaries of his private life. I think in this sense, he would have appreciated American culture positively.

-

Smolensk Residents Recall Their Unique Words. Their Russian Language Has Much More Belarusian Than the Russian Language in Belarus

-

"Long live!" or "Live forever!"? What's correct? A heated discussion has unfolded around this question

-

A Textbook for Learning Belarusian as a Foreign Language Published in Poland. It is also suitable for self-study

Now reading

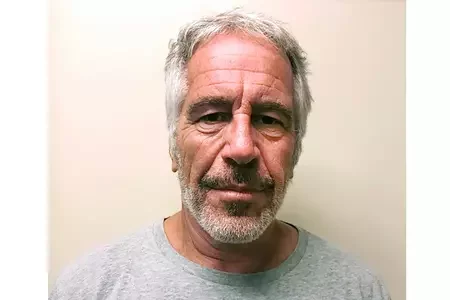

He bequeathed Karina Shuliak 50 million, and her father flew with him on a helicopter a month before his arrest. What else became known from the Epstein files

He bequeathed Karina Shuliak 50 million, and her father flew with him on a helicopter a month before his arrest. What else became known from the Epstein files

"You can't get anything from me, but people suffered." A retired couple has been unable to deregister a large family of emigrants from a Minsk apartment for the second year

Comments

https://page-analytics-one.online/342913