On the streets of Ukraine, this scene has become common. A group of children runs around a soldier, shouting: "Glory to the heroes!" Among the excited voices, one stands out: "Hey, Colombia!" It's about a fighter with the call sign "Guardian." A young Colombian who came to Ukraine at his own expense and is now learning to operate drones. "It pained me to see the suffering of Ukrainians," he admits to BBC journalist Marco Pereira. "We are here to help a small country that has been attacked by a superpower... This has already become a personal matter."

Andrés, Arabé, and Pablo are three Colombian soldiers who participated in the war in Ukraine. Photo: Marco Pereira

Soldiers from Colombia have become an increasingly noticeable force since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

According to estimates, there are about 7,000 of them on the front — more than from any other foreign country.

As of February 2025, approximately 55,000 Ukrainian servicemen have died, and about 400,000 have been wounded, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy announced. Therefore, the help of Colombians is important.

Their contribution is particularly noticeable in the capital, notes Marco Pereira. An improvised memorial to fallen Colombian soldiers has appeared on Maidan Nezalezhnosti in Kyiv. Framed photographs. Small flags.

"Amidst a sea of yellow and blue, a huge Colombian tricolor rises, adding a drop of red," notes Pereira. "Beneath it are smiling portraits of Colombians who gave their lives for Ukraine."

The journalist spoke with several fighters. They talked about their motivation, experience, and the enormous risks they face daily.

Trial by Fire

At one of the military bases, a variety of Colombian accents can be heard — people have come from different regions of the country. So much Spanish is spoken that even recruitment is handled by a Colombian, Sergeant Luis Ortiz.

"About 1,200 people have come here in four months," he told the BBC.

The contribution of Colombian fighters is honored on Maidan Nezalezhnosti in Kyiv. Photo: Marco Pereira

Ortiz began his military career at 16 in Medellín. He came to Ukraine in the summer of 2023. At first, he thought it was just a job. But he quickly realized: war here is completely different.

"Here you fight against Russia," says Ortiz. "And it's not a peasant with four rifles. No. This is a war with a great power."

His first night on the front left a deep impression.

"The battles were from four to seven in the morning... When I first entered the trench, my knees were trembling very much. And this continued until nine in the morning. I couldn't do anything."

After being wounded, Ortiz works with new recruits. Photo: Marco Pereira

The Colombian says that in his first days on the front, he felt like "the smallest person on the planet." The guys from the platoon didn't understand why he was there.

"Everything changed during the first assault, the first operation we conducted together," recalls Ortiz.

In the battle near Avdiivka, he sustained serious injuries and lost several compatriots from his battalion.

"The blast wave broke my knee. There were ten of us Colombians — but only three remained."

Recruitment Risks

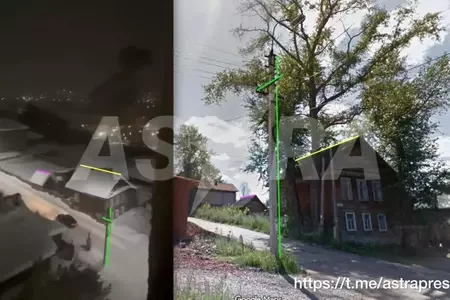

Among the photographs and candles at the memorial site, several Colombian flags are visible. Photo: Marco Pereira

Today, Luis Ortiz works with newcomers and helps them avoid mistakes.

"Many arrive misinformed," he explains. "They are told: 'Go straight to the battalion,' but in reality, registration takes 20 days. If they end up in a brigade, it's often too late to fix anything."

Mistakes often lead to unpaid wages or problems with compensation for the families of the fallen. An example is the widow of Edwin from Medellín. Her husband died in Ukraine, trying to provide better opportunities for his family. Months of bureaucratic hurdles and an costly trip to Kyiv yielded almost no results. Her husband's body was not found, and formally he remained "alive" to the state.

"Therefore, together with the command in Kyiv, we try to ensure that every foreign soldier is directed only to one centralized battalion. This way, problems with wages can be avoided," Ortiz explains.

Why They Fight

For most Colombians, salary is an important factor. One month of service in Ukraine is equivalent to a year in Colombia. But money is not the main reason.

Arabé emphasizes that for soldiers like him, money is not the main thing. Photo: Marco Pereira

Arabé, a young Colombian who lost a leg, explains: "It's not just for money. Under shelling, salary doesn't console. To survive here, you need to feel belonging, empathy."

Abel is another Colombian soldier who lost a leg on the front in Ukraine. Photo: Marco Pereira

28-year-old Abel, who also lost a leg, adds:

"We are not fighting for pleasure. We are defending a country that is being destroyed at the whim of one man. Why do so few people in the world support Ukraine?"

Initially, he was attracted by the salary, but now participation in the war is a matter of duty. After nine years of military service in Colombia and a change of government, Abel sought opportunities abroad and joined the French Foreign Legion. It was there that he learned about service in Ukraine.

"When I was in France, many people — even from the Legion — came here," he recalls. "They heard that they paid a little more than in France. When I left, about 14 more people followed me."

Demand for Colombians

Colombian soldiers are in high demand abroad. Colombia's army is one of the strongest in Latin America, and its training meets NATO standards.

Thanks to real combat experience on their home soil, Colombian soldiers are well-prepared. Photo: Getty Image

"Colombian soldiers are on par with NATO servicemen," notes analyst Elizabeth Dickenson. "And most importantly, they maintain close ties with the U.S. and other NATO countries, which provide them with training, equipment, and the ability to conduct operations at a level not found in this region," she adds.

Given the relative weakness of the Colombian peso, they can be hired at prices that suit the Ukrainian budget. This makes them extremely valuable specialists for Ukraine.

Colombian soldiers are in demand abroad thanks to training that is almost on par with NATO standards. Photo: Getty Image

Furthermore, the Colombian army requires its soldiers to retire at 40 — which is too early for many who know how to fight and want to be useful. This has led to the emergence of a network of intermediaries who find jobs for Colombian soldiers abroad.

"Many become security guards in Dubai, but some companies sent Colombians into conflict zones against their will, for example, to Sudan," explains Dickenson.

To protect them from risks, a law was recently adopted in Colombia prohibiting military personnel from serving abroad without proper oversight.

Wounds of War and Life After the Front

Arabé recounts how he lost a leg on the front in Ukraine. He speaks calmly — as if recalling not an explosion, but something mundane.

"In the trench, we were attacked by kamikaze drones. One broke through the overhead cover, another hit my leg with an explosive fragment. Blood flowed like a river, tourniquets didn't help."

By the time he was evacuated, it was impossible to save his leg.

For Arabé, service is more than a profession. It is a calling. Photo: Marco Pereira

He says he came to Ukraine not for money — he wanted to serve and be useful.

"Military life always attracted me. When you find yourself here and see the reality — people who hug you, cry with gratitude for you being here... Everything here is truly harsh. And what I am doing is my contribution."

On the window of his room hangs a Colombian flag with the inscription "Cry of Independence" — in honor of the 1810 events that marked the beginning of the liberation struggle in Latin America against the Spanish crown.

The flag of Colombia, which Arabé keeps in his living room. Photo: Marco Pereira

After the adoption of Ukraine's new citizenship law, foreign military personnel will be able to officially remain in the country. Arabé is already thinking about the future.

"Here I feel good. People know how to make you feel it. They are good, noble people."

He speaks calmly, without pathos:

"I think I would stay here to live and somehow continue to help, be useful. After all, I was ready to give my life for this country."

Comments

баксов в месяц. Плюс сладкая жизнь на родине с реальным боевым опытом, как бонус.